Foundation Models for Sequential Decision-Making

In this post, I'm hoping to give some sort of timeline of advances made in fields like reinforcement learning and robotics that I believe could be important to know about or might be important to realize AI embodied in the real world.e will start by reviewing some classical papers that combine Transformers with reinforcement learning for multi-task control. Then, we will look at some more recent advances that are used in simulated open-ended environments, and from there on we will move on to advances in control for real-world robotics with robotics foundation models.

In this post, I was hoping to give some sort of timeline of advances made in fields like reinforcement learning and robotics that I believe could be important to know about or might be important to realize AI embodied in the real world. We will start by reviewing some classical papers that combine Transformers with reinforcement learning for multi-task control. Then, we will look at some more recent advances that are used in simulated open-ended environments, and from there on we will move on to advances in control for real-world robotics with robotics foundation models. Finally, we will talk about some challenges that these current approaches have and what future opportunities exist for people interested in the field.

Discussed topics:

-

(Multi-Game) Decision Transformers.

-

Foundation Models for Sequential Decision-Making.

-

Example of Foundation Models in Massively Open-Ended Environments.

-

Foundation Models and Robotics.

Classical Papers: Transformers for Reinforcement Learning

In this section, we will talk about two classical papers in the field of reinforcement learning that were the first working approaches that utilized transformers as a backbone for (multi-game) control.

Decision Transformers (2021)

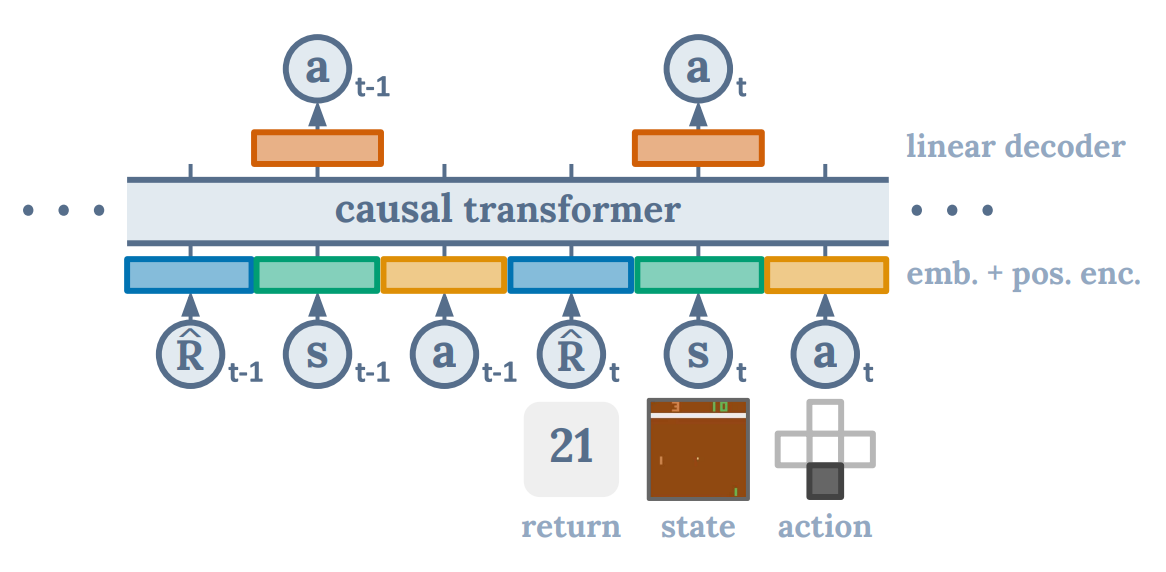

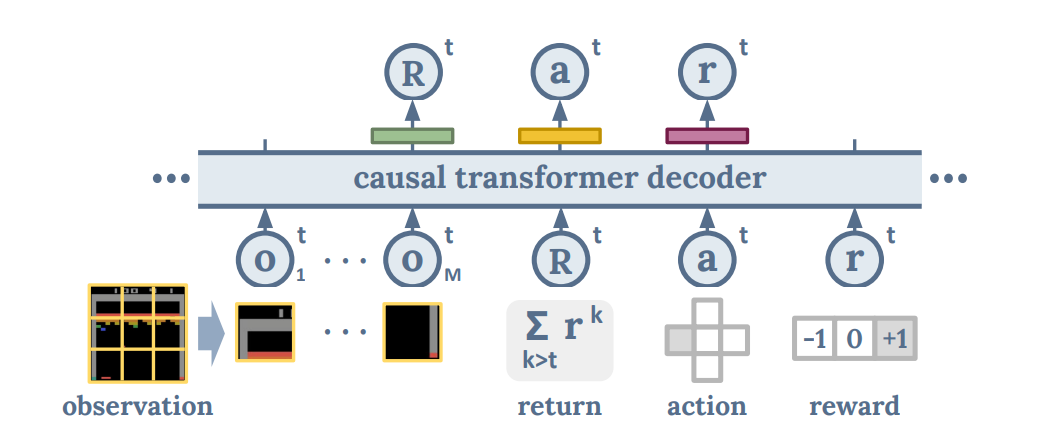

The first paper, called the Decision Transformer [1], acknowledges that reinforcement learning can trivially be framed as a sequence modelling problem. Your sequence would consist of observation, action, reward, and terminal state tokens. In the paper, instead of using the rewards, the authors decide to use the return-to-go, $\hat{R_t} = \sum_{t^\prime = t}^T r_{t^\prime}$, since it pre-trains on trajectories that were collected beforehand, so they can be computed. This means that the method does not train online! Their sequences look as follows:

\[\tau = (\hat{R_1}, s_1, a_1, \hat{R_2}, s_2, a_2, \dots, \hat{R_T}, s_T, a_T)\;.\]Note: If you would do this in an online settings, you would need to estimate the return, since you cannot compute the return-to-go’s. This makes it a lot more difficult, and current methods struggle with this!

Architecture and Training

In the figure above, you can see how these sequences are encoded into a causal transformer. Note that each modality (e.g. return, state, and action) are encoded with their own embedding scheme, since different modalities might benefit from different embeddings. In addition to this embedding, they add a positional embedding that is per-timestep. In contrary to text-based models, one timestep in this sequence is a 3-tuple $(\hat{R}_t, s_t, a_t)$, so these receive the same positional embedding.

The model attempts to predict actions using a linear decoder on top of the observation encodings of the Transformer backbone. The model is trained using a simple behaviour cloning loss, which is the mean-squared error between prediction and actual actions. One model is trained per environment, so it is not a multi-task method!

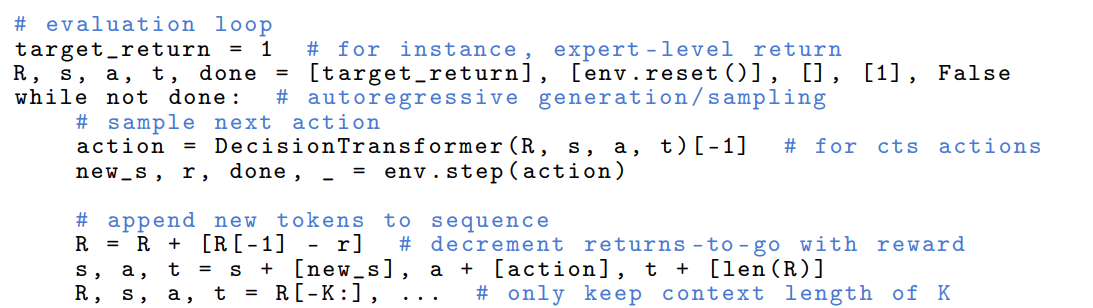

Inference (Online)

Since you want the model to output actions with the highest estimated return-to-go, you cannot simply sample actions naively from the transformer. Furthermore, you do not have these return-to-go’s at inference time, since you are now running online experiments, and you do not know your return in advance.

In the paper, the authors normalized the returns to be in a $[-1, 1]$ range. Hence, by manually setting the first return-to-go $\hat{R}_1 = 1$, you are explicitly conditioning the model to generate the actions are yield the highest return-to-go.

Experiments and Results

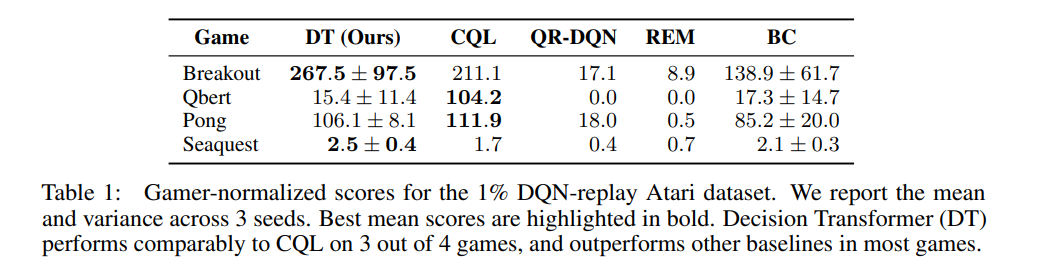

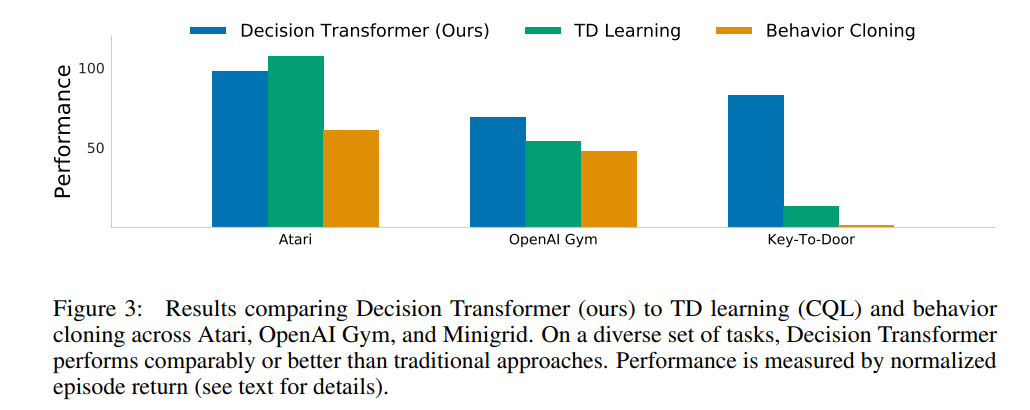

The authors evaluated this method on an offline reinforcement learning dataset for Atari called the DQN-Replay Atari dataset and benchmarked it against various offline reinforcement learning algorithms. The method seems to perform comparably to CQL, a powerful offline RL method, for 3 out of 4 games, which is not bad given the simplicity of the method!

They also benchmark on some other environments where CQL and BC do not perform as well, and show the consistency of their method across multiple tasks!

Multi-Game Decision Transformers (2022)

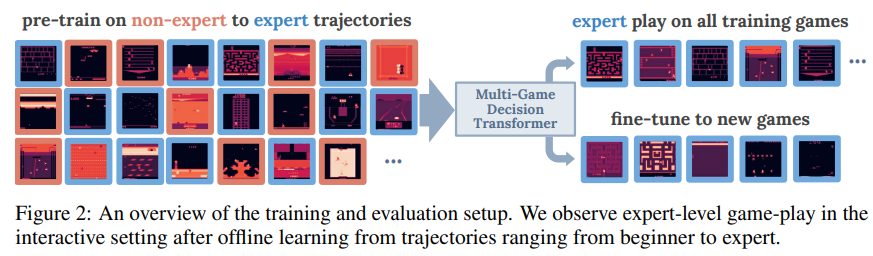

The follow-up work [2] on the Decision Transformer paper tries to develop a multi-game agent that has a Transformer backbone, which they call the “Multi-Game Decision Transformer”. The setting stays similar to the original paper; the model is still pre-trained using datasets of trajectories that are collected by policies of various skill levels. In this paper, the Transformer is also scaled to up to $200$M parameters.

In contrast to the original paper, this approach tries to do meta-learning: after pre-training a model, you should be able to use it to efficiently fine-tune the parameters to new games. This concept is quite similar to how you can fine-tune LLMs for task-specific purposes.

In this paper, the sequence is constructed in a slightly different manner:

\[\tau = (\dots, o_t^1, \cdots o_t^M, \hat{R}_t, a_t, r_t, \cdots)\;.\]Note that the return-to-go is no longer at the front of the sequence. Furthermore, there are multiple observation tokens $o_t^1, \cdots, o_t^M$ that correspond to $M$ tokenized patches in the image observations. They also include the rewards in the trajectory sequence. This design allows predicting the return distribution and sampling from it, instead of relying on a user to manually select an expert-level return at inference time.

They also scale the reward in a $[-1, 1]$ range and quantize the returns into bins of ${-20, -19, \cdots, 100}$.

Training

The paper focusses on evaluation in the Atari domain. They also use the DQN-Replay Atari dataset, from which they select $41$ games for training and $5$ holdout games for out-of-distribution generalization. For each game, they use $50$ policy checkpoints which each contain $1,000,000$. In total, this corresponds to $4.1$ billion environment steps.

Inference (Online)

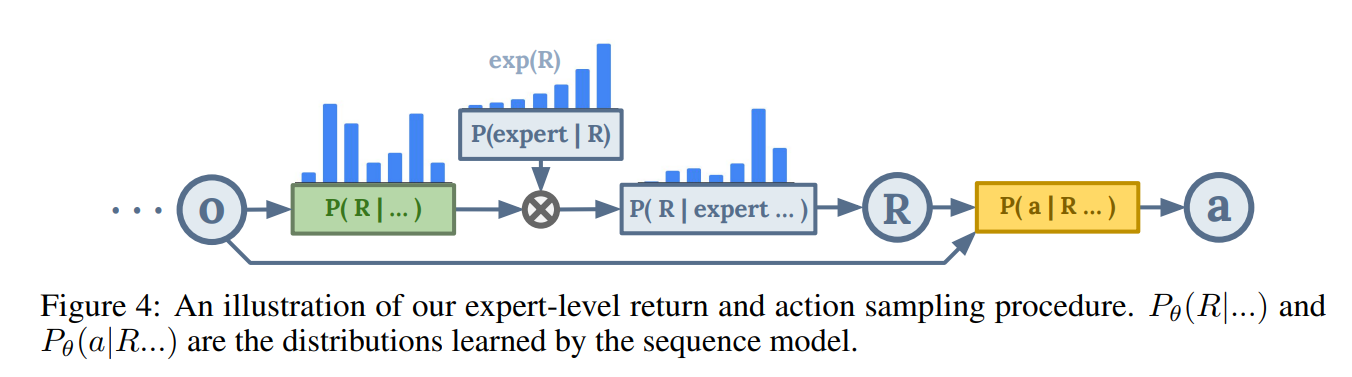

As described above, the training datasets contain a mix of expert and non-expert behaviours, thus directly generating actions from the model imitating the data is unlikely to consistently produce expert behaviour.

Instead, the authors propose an inference-time method of sampling actions that are estimated to have a high return-to-go. They assume there is a binary classifier $P(\mathrm{expert}_t \vert \dots)$ that classifies whether a behaviour is expert-level before taking an action $a_t$. This can be written as:

\[P(\mathrm{expert}_t \vert R_t) \propto \exp(\kappa \frac{R_t - R_{\mathrm{low}}}{R_{\mathrm{high}} - R_{\mathrm{low}}})\;.\]

We want to sample a return $R$ so we can continue sampling actions at inference time, since we do not have access to a return-to-go. Hence, we want to model a distribution $P(R_t \vert\mathrm{expert}_t)$. We will do this using Bayes’ rule:

\[P(R_t \vert\mathrm{expert}_t) \propto P(\mathrm{expert}_t \vert R_t)P(R_t \vert \cdots)\\ \log P(R_t \vert\mathrm{expert}_t) \propto \log P(R_t \vert \dots) + \kappa \frac{R_t - R_{\mathrm{low}}}{R_{\mathrm{high}} - R_{\mathrm{low}}}\;.\]Using these two distributions, you can now sample $R_t$ from $P(R_t \vert\mathrm{expert}_t)$ and obtain expert-level trajectories. This is also depicted in the figure above.

Experiments and Results

The nice thing about this paper is that it has very extensive results on the Atari domain, which we will take a look at here. They ask the following questions:

-

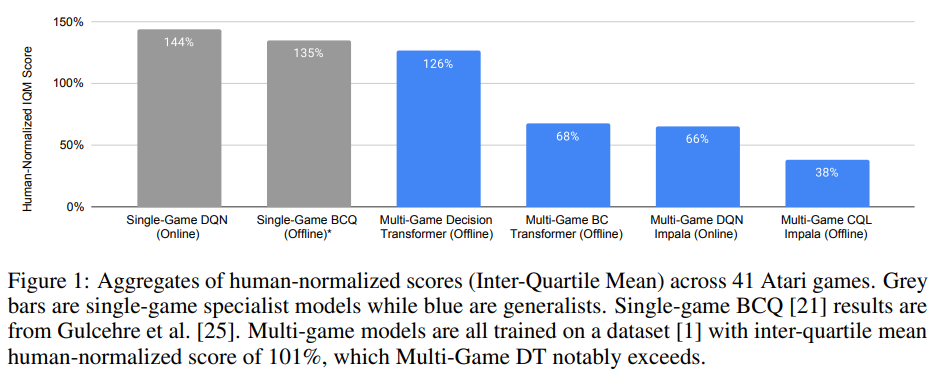

How do different online and offline methods perform in the multi-game regime?

The single-game specialists are still most performant. Among multi-game generalist models, the Multi-Game Decision Transformer model comes closest to specialist performance. Multi-game online RL with non-transformer models comes second, while they struggled to get good performance with offline non-transformer models.

-

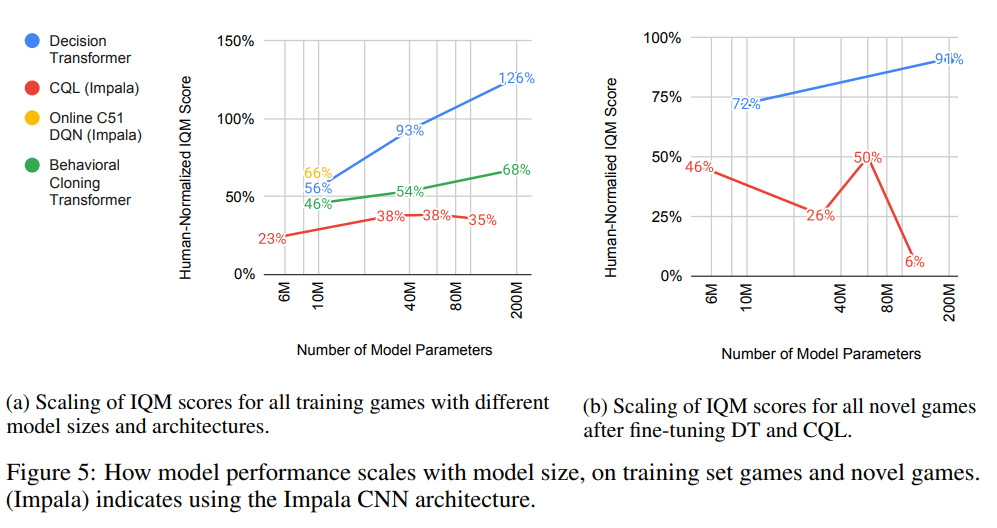

How do different methods scale with model size?

Multi-Game Decision Transformer performance reliably increases over more than an order of magnitude of parameter scaling, whereas the other methods either saturate, or have much slower performance growth.

-

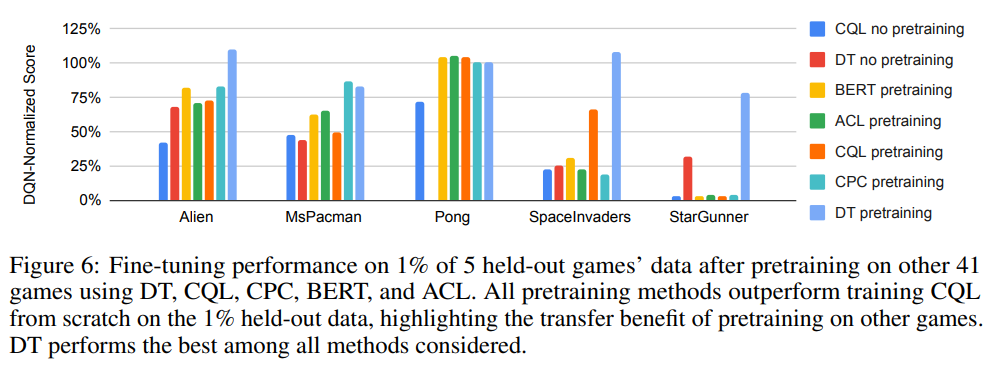

How effective are different methods at transfer to novel games?

Pretraining with the DT objective performs the best across all games. All methods with pretraining outperform training CQL from scratch, which verifies the hypothesis that pretraining on other games should indeed help with rapid learning of a new game

-

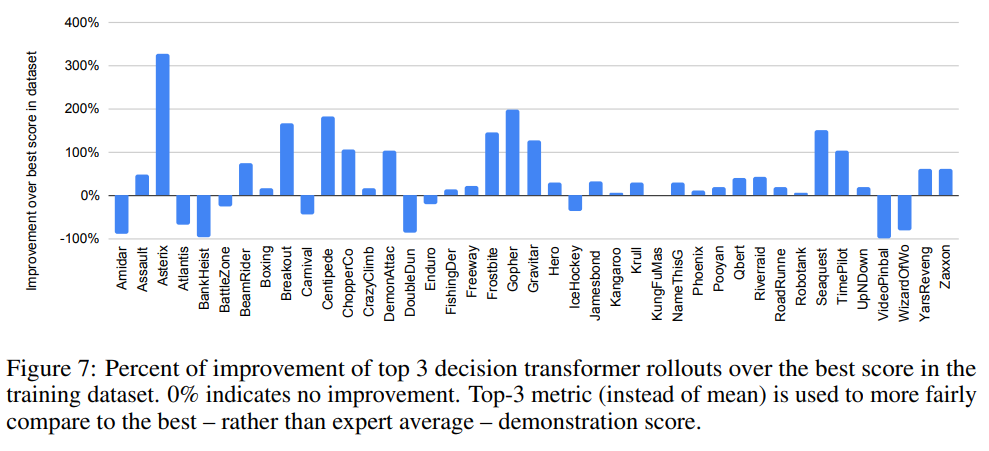

Does expert action inference improve upon behavioural cloning?

Using sampling expert behaviours, they see significant improvement over the training data in a number of games.

-

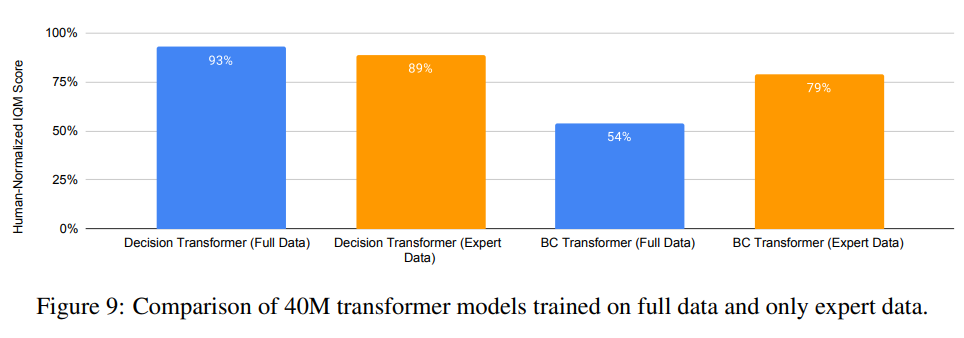

Does training on expert and non-expert data bring benefits over expert-only training?

They observe that (1) Training only on expert data improves behavioural cloning; (2) Training on full data, including expert and non-expert data, improves Decision Transformer; (3) Decision Transformer with full data outperforms behavioural cloning trained on expert data.

Foundation Models for Sequential Decision-Making (2023)

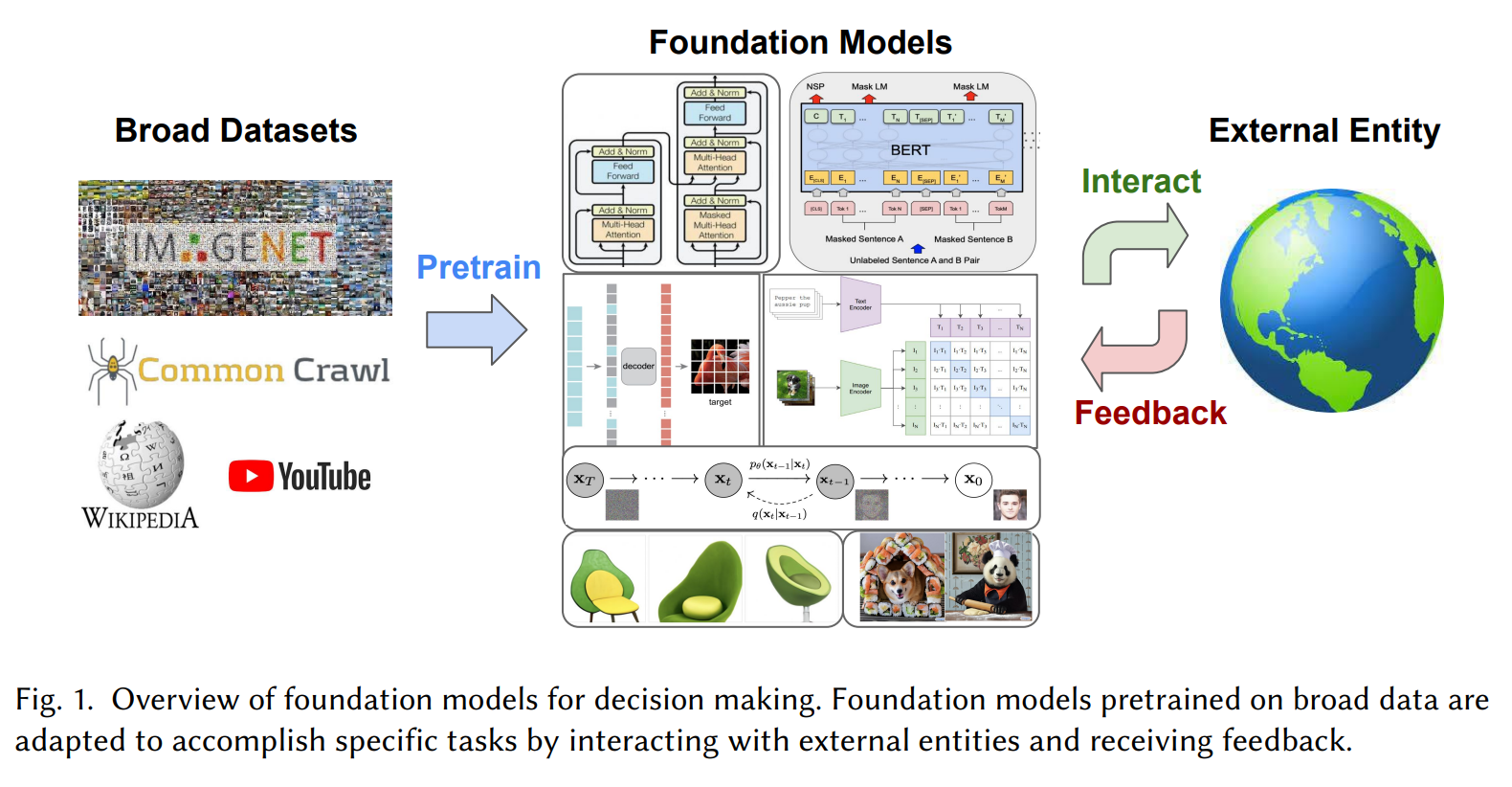

Now that we have seen some classical approaches to doing reinforcement learning with Transformers with models that scale up to $200$M parameters, we will take a look at approaches that utilize (multi-modal) foundation models for sequential decision-making. This section will be based on a great survey [3] to help relate this topic to what we have seen in the classical approaches. The following is the motivation behind this survey:

Foundation models, which are trained on vast and varied data, show great potential in vision and language tasks and are increasingly used in real-world settings, interacting with humans and navigating environments. New training paradigms are developing to enhance these models’ ability to engage with other agents and perform complex reasoning, utilizing large, multimodal datasets. This survey explores how foundation models can be applied to decision making, presenting conceptual and technical resources to guide research. It also reviews current methods like prompting and reinforcement learning that integrate these models into practical applications, highlighting challenges and future research opportunities.

On a high level, the goal is to enable pre-trained foundation models to quickly accomplish decision-making problems by interacting with an environment or external entity, similar to reinforcement learning.

Generative Models of Behaviour

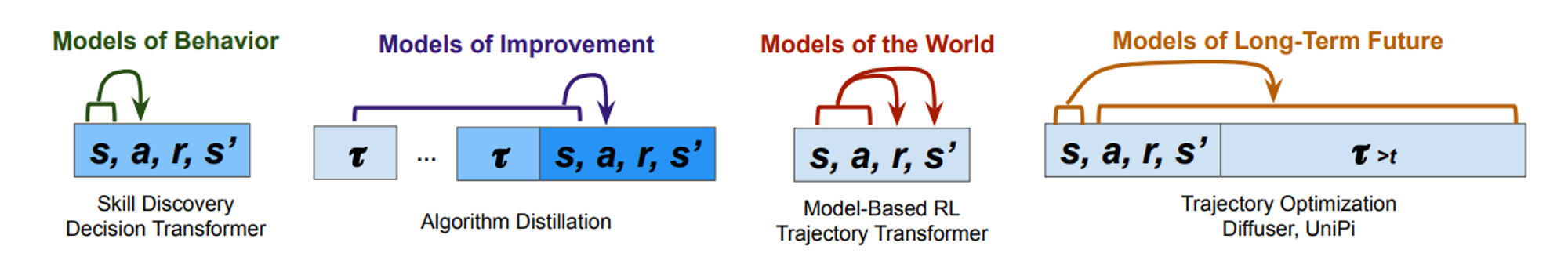

Generally, generative models are applied to static text or image data $x \in \mathcal{D}$. On the other hand, for decision-making, you are concerned with task-specific interactive data $\tau \in \mathcal{D}_\mathrm{RL}$, which often distinguishes states, actions, and reward labels.

If you want to build a generally capable systems, your dataset will need to include diverse behaviours. For example, in robotics, you might need a set of so-called behaviour priors such as “pick up objects” or “move objects” which can be composed to complete tasks. As we saw in the classical approaches, usually a model is fit using an imitation learning objective.

The figure above shows some different ways of modelling behaviours, improvements, environment, and long-term futures given trajectories $\tau$. Unfortunately, many of these approaches rely on near-expert data to perform well, often due to limits in extrapolation beyond the training dataset.

Luckily, one key advantage to generative modelling of behaviour lies in scaling up: even though tasks often have different observations and rewards, there are often shared meaningful behaviours across different tasks. This makes it worth it to train agents on massive behaviour datasets, since they might extract generalizable behaviours from them.

- One way of scaling and training generalizable models is through combining multiple task-specific datasets $\mathcal{D}_\mathrm{RL}$, but in the real world, there is a lack of data that is directly posed in such a way that it can be frames as a reinforcement learning problem.

- Instead, it might be worth it to look into exploiting internet-scale text and video data for training these models, since there is an abundant quantity of this data. The main downside is that this data often does not have explicit actions or numerical rewards. Nevertheless, you can still extract useful behaviour priors from them. This works because goals are often also formulated in natural language, even though this means that they can be quite sparse. One example of this is the goal “Mine diamonds” in Minecraft. Multiple papers have approached this problem in unique ways. For example, GATO [4] approach this issue with universal tokenization, so that data without actions can be jointly trained using large sequence models. Other approaches try to apply inverse dynamics to label large video data [5, 6].

- Another approach that has been used a lot in the past is large-scale online learning, which typically uses access to massive online game simulators such as DoTA, StarCraft, and Minecraft. The agents that are trained on these environments are typically optimized using online reinforcement learning.

Furthermore, generative models of behaviour can also be extended to model meta-level processes, such as exploration and self-improvement if the dataset itself contains these behaviours.

Similar to algorithm distillation, which prompts an agent with its prior learning experience, corrective re-prompting also treats long-horizon planning as an in-context learning problem, but uses corrective error information as prompts, essentially incorporating feedback from the environment as an auxiliary input to improve the executability of a derived plan. [7]

Foundation Models as Representation Learners

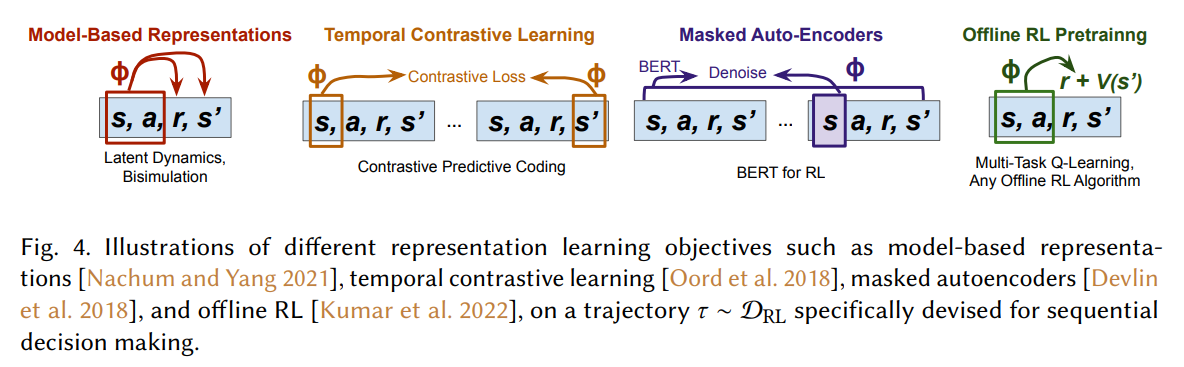

As we saw, one way to use foundation models for decision making is by leveraging representation learning for knowledge compression. On one hand, foundation models can extract representations from broad image and text data, $D$, resulting in a plug-and-play style of knowledge transfer to vision and language based decision making tasks. On the other hand, foundation models can also be used to support task-specific representation learning via task-specific objectives and interactive data, $\mathcal{D}_\mathrm{RL}$.

- Plug-and-Play: Off-the-shelf foundation models pretrained on Internet-scale text and image data can be used as pre-processors or initializers for various perceptual components of decision making agents.

- Even in the case where an agent’s states, actions, and rewards do not consist of images or text, pretrained language models, perhaps surprisingly, have still been found useful as policy initializers for offline RL [8], online RL [9], and structured prediction tasks [10].

- Vision and Language as Task Specifiers: An important special case of plug-and-play foundation models is to use text commands or visual inputs as task specifiers to learn more robust, general, and multi-task policies.

- Using vision and language task specifiers to prompt for desirable agent behaviours requires additional data such as text descriptions or goal images of a given task.

- However, prompting for desirable outcomes from a large language model has significant potential but is also an open problem in itself, whose complexity is exacerbated in decision making scenarios with external entities and world dynamics.

Unlike vision-language foundation models that can learn from a broad data collection $D$ but lack the notion of decision making, foundation model techniques and architectures (as opposed to the pretrained models themselves) can be used to optimize objectives uniquely devised for sequential decision making on the basis of task-specific interactive data $D_\mathrm{RL}$. The figure above visually illustrates different representation learning objectives.

One important thing to note is that unlike generative foundation models that can directly produce action or next state samples, foundation models as representation learners are only directed to extract representations of states, actions, and dynamics; hence they require additional finetuning or model-based policy optimization to achieve strong decision making performance.

Large Language Models as Agents and Environments

In this section, we consider a special case where pretrained large language models can serve as agents or environments. Treating language models as agents, on one hand, enables learning from environment feedback produced by humans, tools, or the real world, and on the other hand enables new applications such as information retrieval and web navigation to be considered under a sequential decision making framework.

There are a few different ways that LLMs can be used and are currently used as agents and environments:

- Interacting with humans: You can frame the dialogue as an MDP and optimize dialogue agents using alignment techniques. Here, you have task-specific dialogue data $\mathcal{D}_\mathrm{RL}$.

- Interacting with Tools: Language model agents that generate API calls (to invoke external tools and receive responses as feedback to support subsequent interaction) can be formulated as a sequential decision making problem analogous to the dialogue formulation.

- Language Models as Environments: Iterative prompting can be characterized as an MDP that captures the interaction between a prompt provider and a language model environment. Under this formulation, various schemes for language model prompting can be characterized by high-level actions that map input strings to desired output strings using the language model.

Foundation Models for Minecraft

Minecraft is an amazing game for the evaluation of embodied life-long learning agents, since it’s an open-ended open-world game that consists of a lot of possible tasks. These tasks can be rather easy, such as building a simple house, or more complicated like finishing the game’s storyline. The MineRL [11] competition was a competition track at NeurIPS where people have to build agents that solve various problems in the domain of Minecraft. These are some prior challenges and suites for the game:

- MineRL Diamond Competition (2019, 2020, 2021): The challenge was to develop an AI agent capable of obtaining a diamond in Minecraft, emphasizing sample-efficient reinforcement learning.

- BASALT (2022): Focused on agents learning from human feedback and demonstrations without rewards. The tasks included finding a cave, building a village house, and more.

- MineDojo (2022): A framework built for embodied agent research. It features a simulation suite with 1000s of open-ended and language-prompted tasks, where the AI agents can freely explore a procedurally generated 3D world with diverse terrains to roam, materials to mine, tools to craft, structures to build, and wonders to discover.

Voyager (2023)

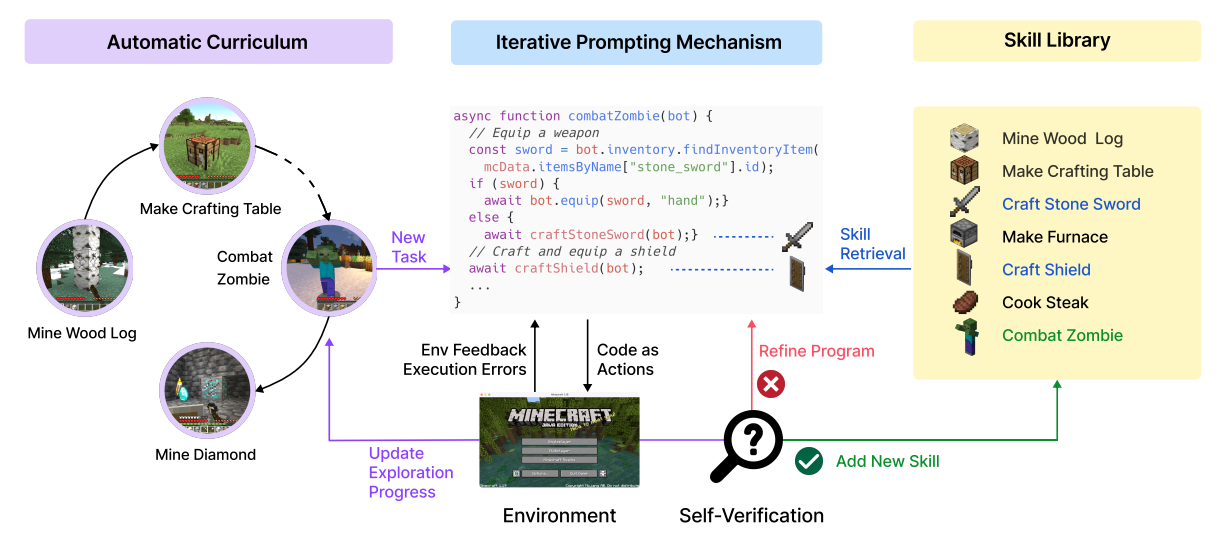

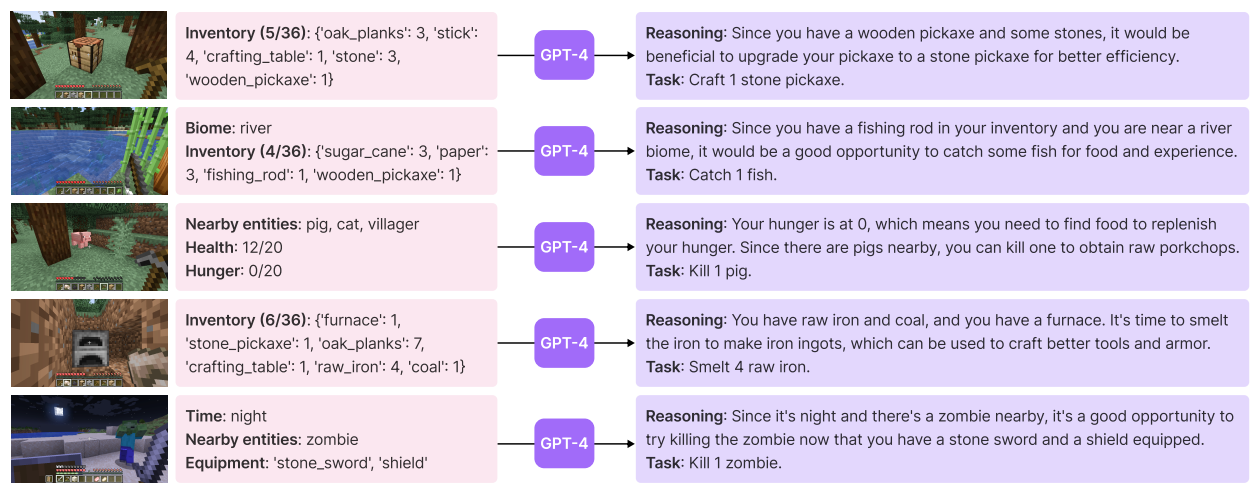

Voyager [12] by NVIDIA is the first LLM-powered embodied lifelong learning agent in Minecraft that continuously explores the world, acquires diverse skills, and makes novel discoveries without human intervention! It related to the previous section on LLMs as agents, as it interacts with GPT-4 via black-box queries. It consists of three components:

-

An automatic curriculum that maximizes open-ended exploration.

The model is able to automatically construct new tasks in the curriculum by querying GPT-4, which comes up with tasks on an appropriate difficulty.

-

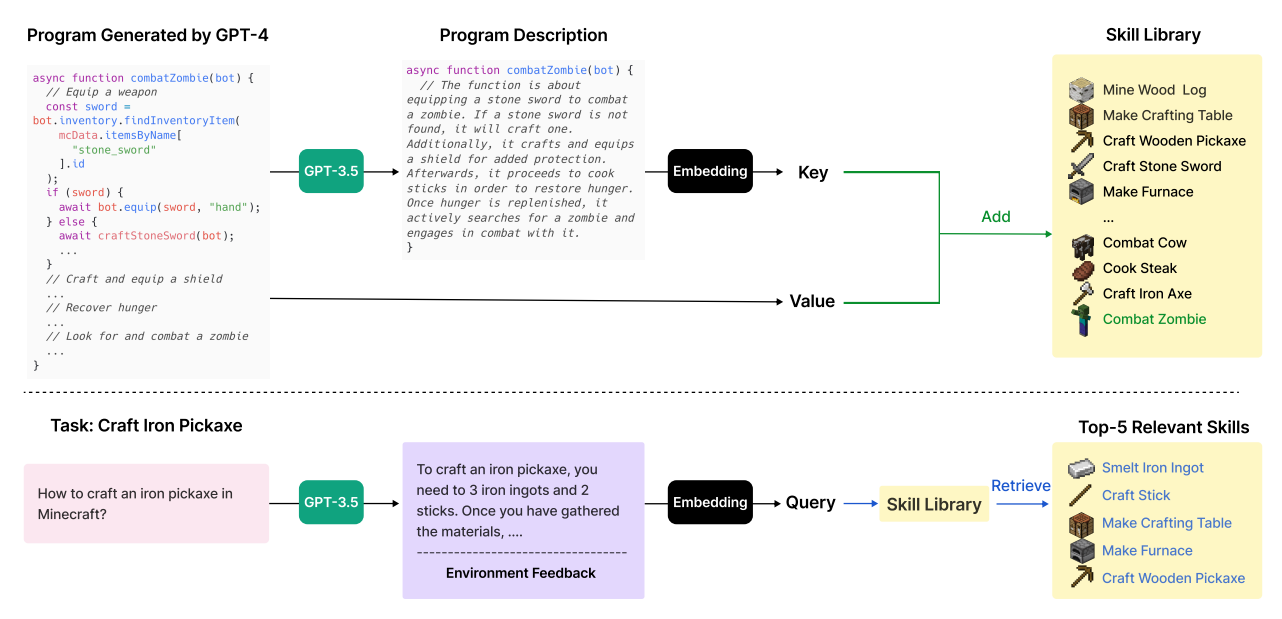

An ever-growing skill library of executable code for storing and retrieving complex behaviours.

Each time GPT-4 generates and verifies a new skill, they add it to the skill library, represented by a vector database. The key is the embedding vector of the program description (generated by GPT-3.5), while the value is the program itself.

When faced with a new task proposed by the automatic curriculum, they first leverage GPT-3.5 to generate a general suggestion for solving the task, which is combined with environment feedback as the query context. Subsequently, they perform querying to identify the top-5 relevant skills.

-

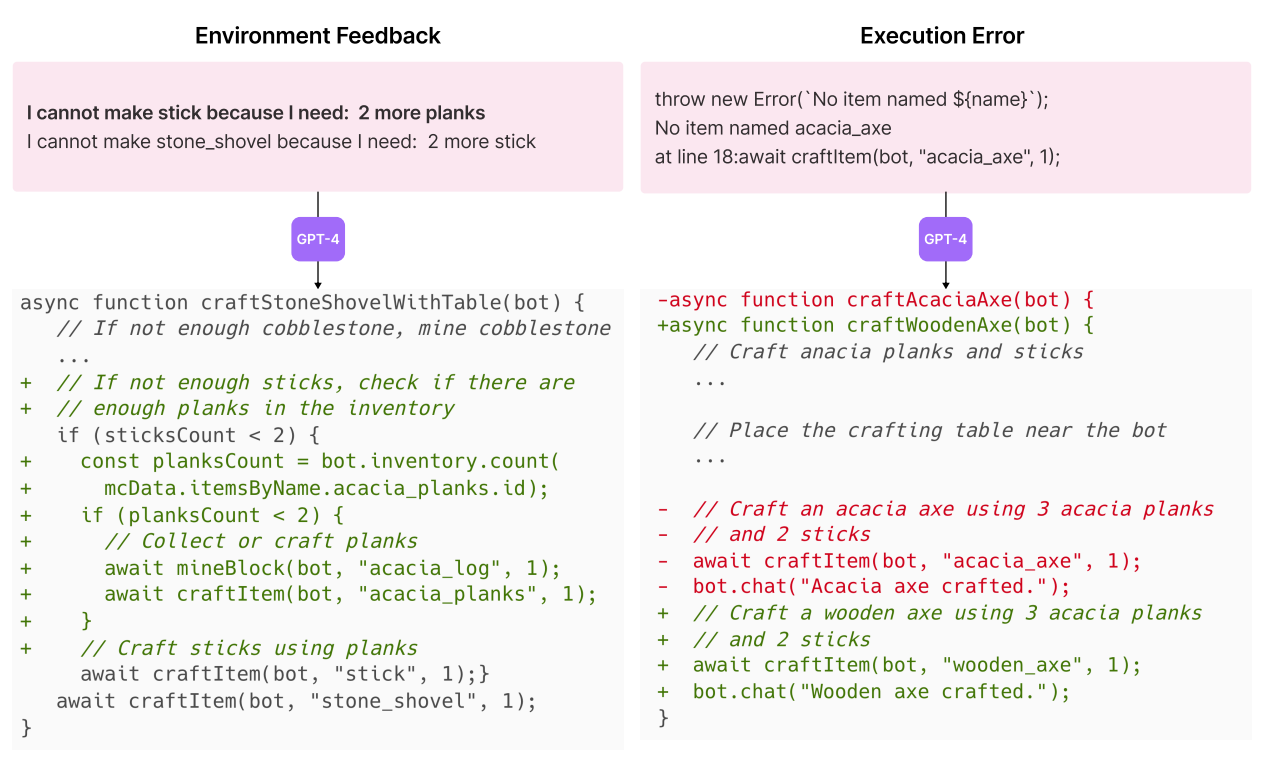

A new iterative prompting mechanism that incorporates environment feedback, execution errors, and self-verification for program improvement.

Instead of manually coding success checkers for each new task proposed by the automatic curriculum, they instantiate another GPT-4 agent for self-verification. By providing VOYAGER’s current state and the task to GPT-4, they ask it to act as a critic and inform them whether the program achieves the task. In addition, if the task fails, it provides a critique by suggesting how to complete the task.

Experiments and Results

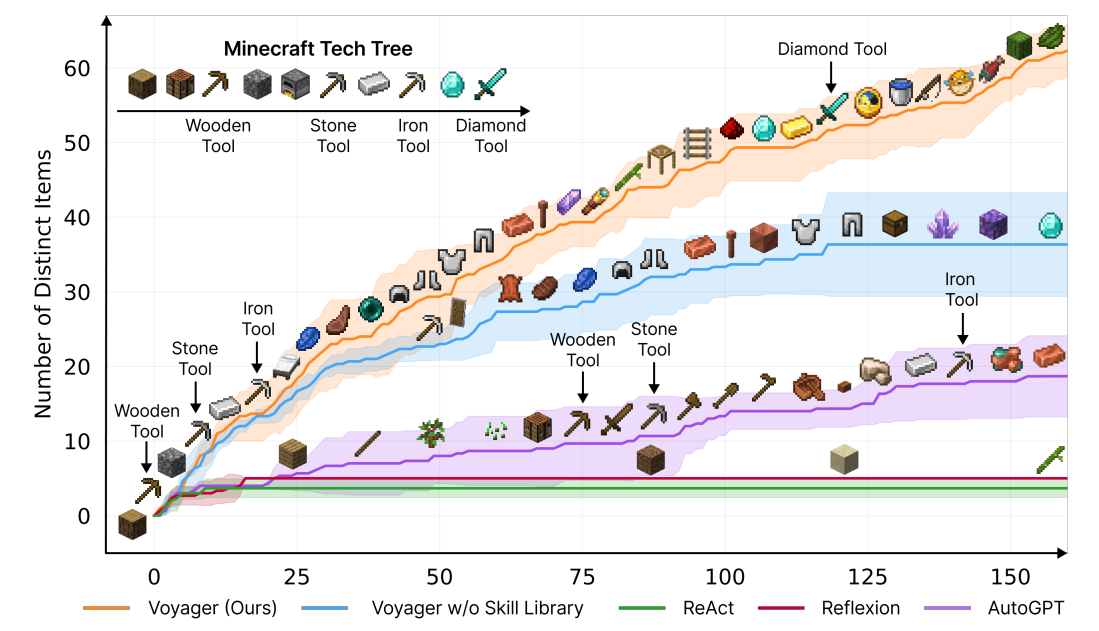

The experiments have very good results; they achieve a new state-of-the-art in all of the benchmarks for Minecraft among other LLM-based agents, especially regarding long tasks that require a specific curriculum to achieve.

- Their method is able to unlock components of the tech tree that are quite involved, which other methods are nowhere close to achieving.

- The method is able to explore and traverse diverse terrains for $2.3$x longer distances compared to baselines.

MineDreamer (2024)

This [13] is a very recent (Mar 2024) approach, which I wanted to discuss as it is more similar to the previous section on Foundation Models as Representation Learners.

The method essentially addresses the issue that foundation models for sequential decision-making struggle to enable agents to follow textual instructions steadily, due to the fact that:

- Many textual instructions are abstract for low-level control and models struggle to effectively understand.

- Many textual instructions are sequential, and executing them may require considering the current state and breaking down the task into multiple stages for step-by-step completion.

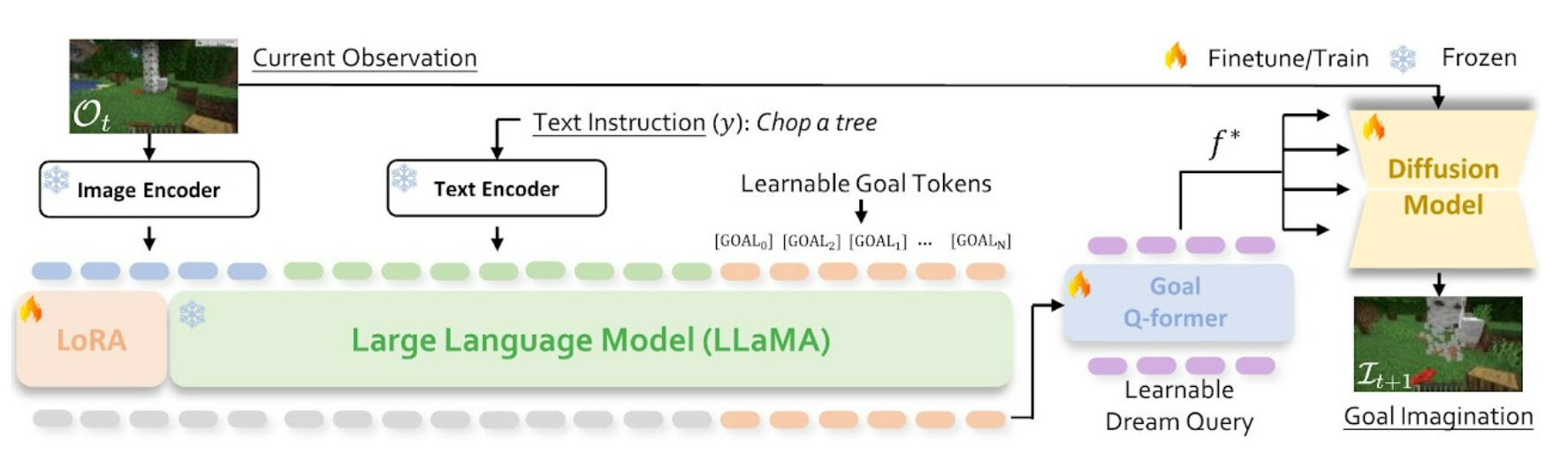

On a high level, instead of using a pre-trained LLM as an agent, they fine-tune LLaVa to output goals and introduce the idea of Chain-of-Imagination to address the above issues.

The architecture this model, which they call the imaginator, encodes the current environment observation along with a textual task instruction. For goal understanding, they add $k$ [GOAL] tokens to the end of instruction and input them with current observation into LLaVA. Then LLaVA generates hidden states for the [GOAL] tokens, which the Q-Former processes to produce the feature $f^*$. Subsequently, the image encoder combines its output with $f^*$ in a diffusion model for instruction-based future goal imagination generation.

This allows MineDreamer to decompose its potentially sparse problem instruction into feasible subgoals, which are imaged using diffusion. An overview of the Chain-of-Imagination mechanism is depicted in the figure below:

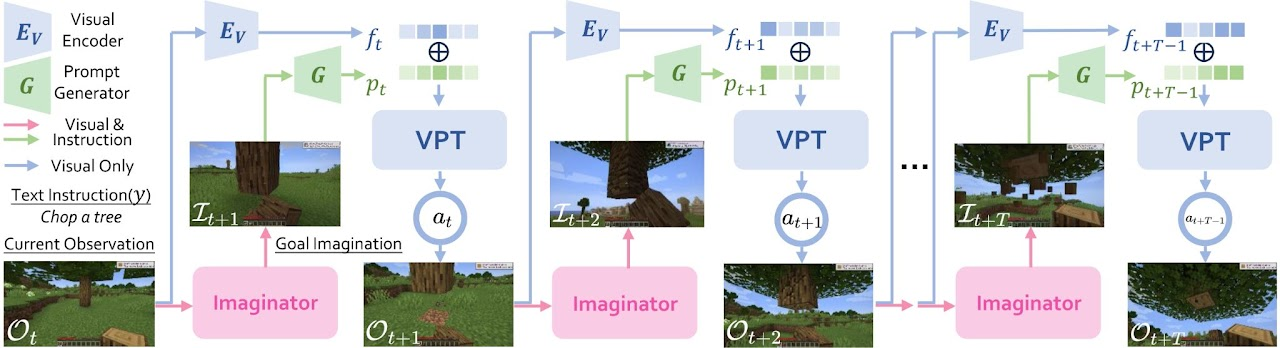

The imaginator imagines a goal imagination based on the instruction and current observation. The Prompt Generator transforms this into a precise visual prompt, considering both the instruction and observed image. The Visual Encoder encodes the current observation, integrates it with this prompt, and inputs this into VPT, a video-pretrained model. VPT then determines the agent’s next action, leading to a new observation, and the cycle continues.

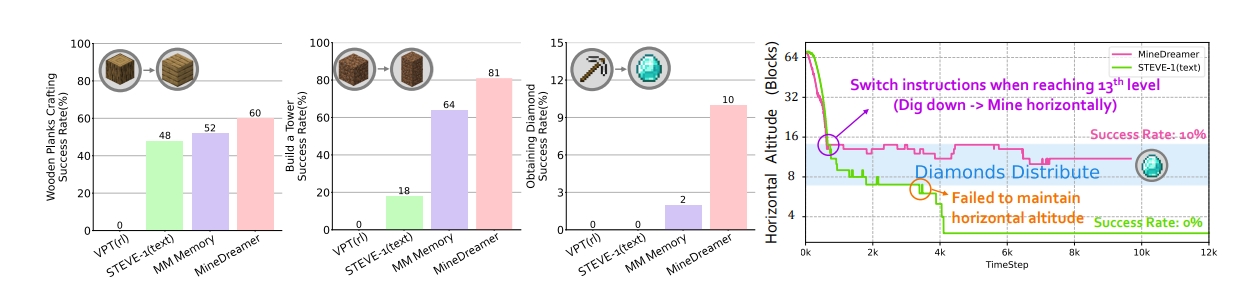

Experiments and Results

Interestingly, the method appears to swiftly adapt to new instructions and achieves higher success rates than any other fine-tuned method. It also shows that the method is great for command-switching for long-horizon tasks, as it surpasses previous methods by quite a large margin. This can be seen in the figure below.

Foundation Models and Robotics

In this last section of papers, we will briefly look at various works that try to train generalist robotics policies.

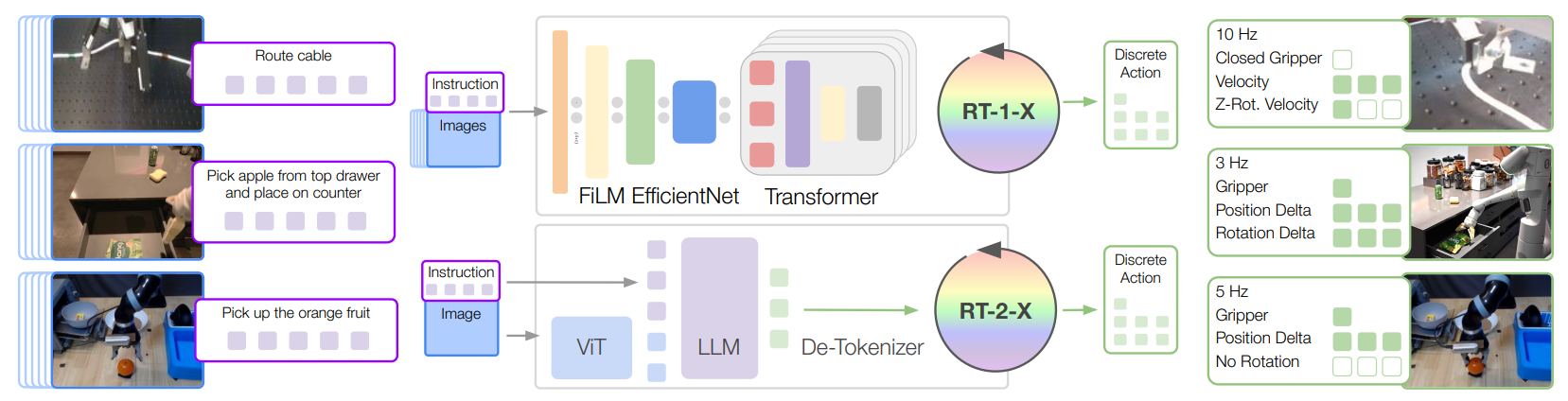

Open-X Embodiment (2023)

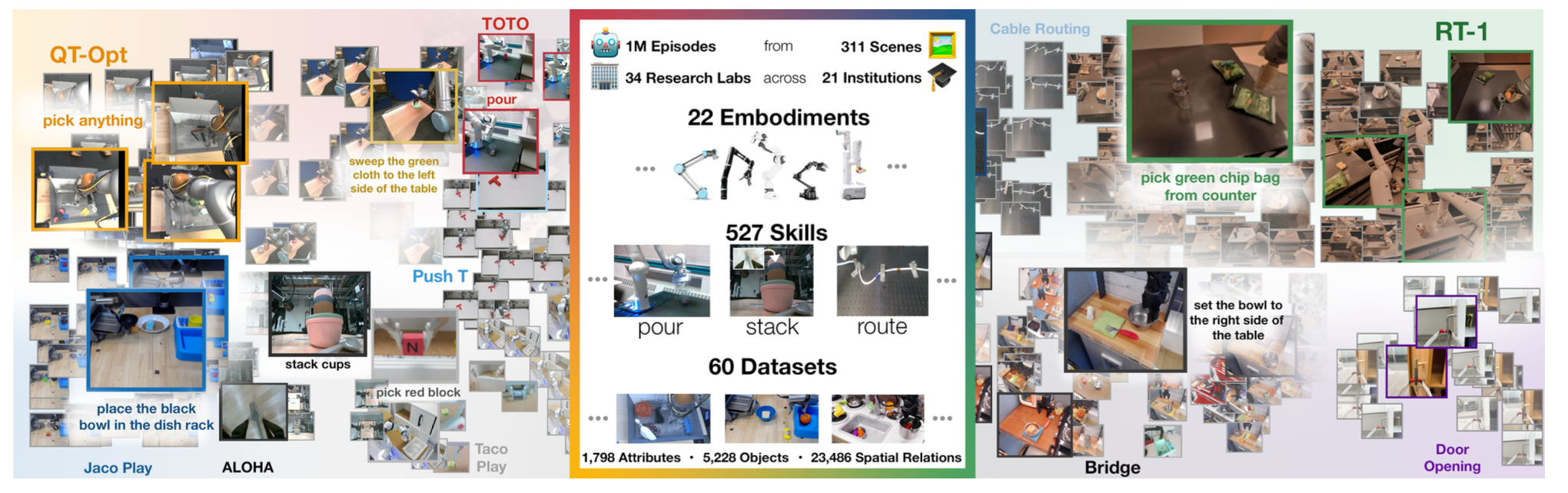

Robotics comes with a unique problem: Conventionally, robotic learning methods train a separate model for every application, every robot, and even every environment. One big question is whether it is possible to train a “generalist” X-robot policy that can be adapted efficiently to new robots, tasks, and environments? Unfortunately, there is not enough data to pre-train a policy for this goal. For this reason, many companies and academic labs formed a joint collaboration to develop the Open-X Embodiment dataset [14]. This is a massive dataset with currently $22$ embodiments, $527$ skills, and $60$ datasets, consisting of a total of $160,266$ tasks.

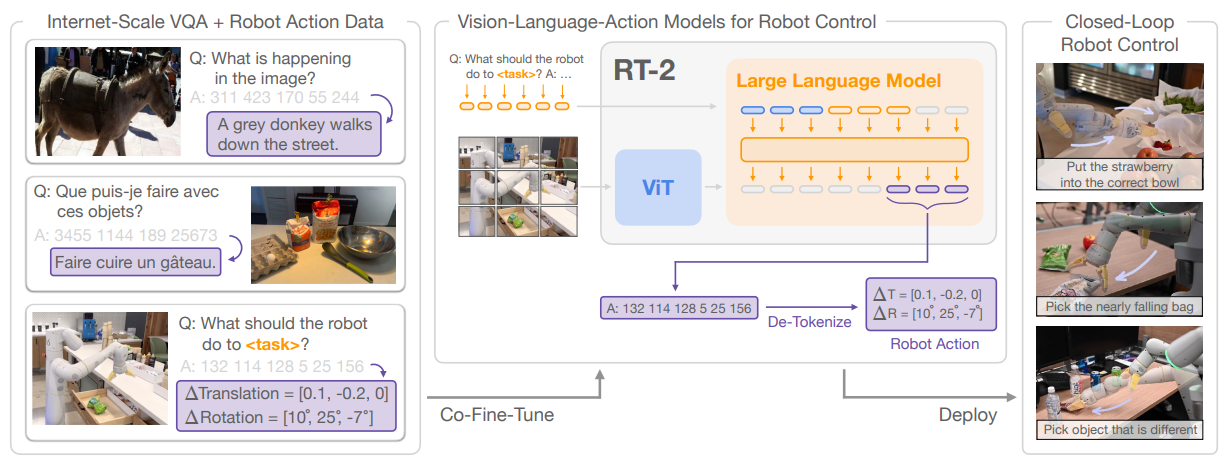

They train a high-capacity model called “RT-2-X” on this dataset, and show that it exhibits positive transfer between embodiments, tasks, and improves on the capabilities of several robotics. The model takes images and a text instruction as input and outputs discretized end-effector actions.

The way it does this is through fine-tuning a model called “RT-2”. This model, introduced in [15], is a family of large vision-language-action models (VLAs) trained on Internet-scale vision and language data along with robotic control data. RT-2 casts the tokenized actions to text tokens, e.g., a possible action may be “1 128 91 241 5 101 127”. As such, any pretrained vision-language model can be finetuned for robotic control, thus leveraging the backbone of VLMs and transferring some of their generalization properties. A figure that visualizes this method is depicted below.

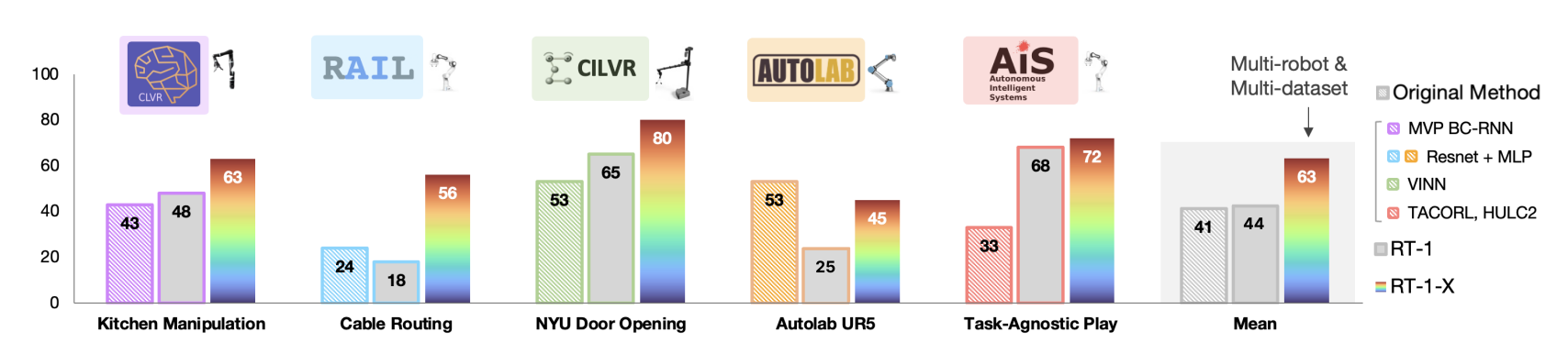

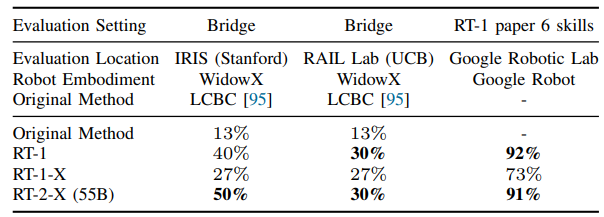

Experiments and Results

The RT-1-X mean success rate is $50$% higher than that of either the Original Method or RT-1. The performance increase can be attributed to co-training on the robotics data mixture. The lab logos indicate the physical location of real robot evaluation, and the robot pictures indicate the embodiment used for the evaluation.

For large-scale datasets (Bridge and RT-1 paper data), RT-1-X underfits and performs worse than the Original Method and RT-1. RT-2-X model with significantly many more parameters can obtain strong performance in these two evaluation scenarios.

In summary, the results showed that the RT-1-X policy has a $50$% higher success rate than the original, state-of-the-art methods contributed by different collaborating institutions, while the bigger vision-language-model-based version (RT-2-X) demonstrated ∼$3$× generalization improvements over a model trained only on data from the evaluation embodiment.

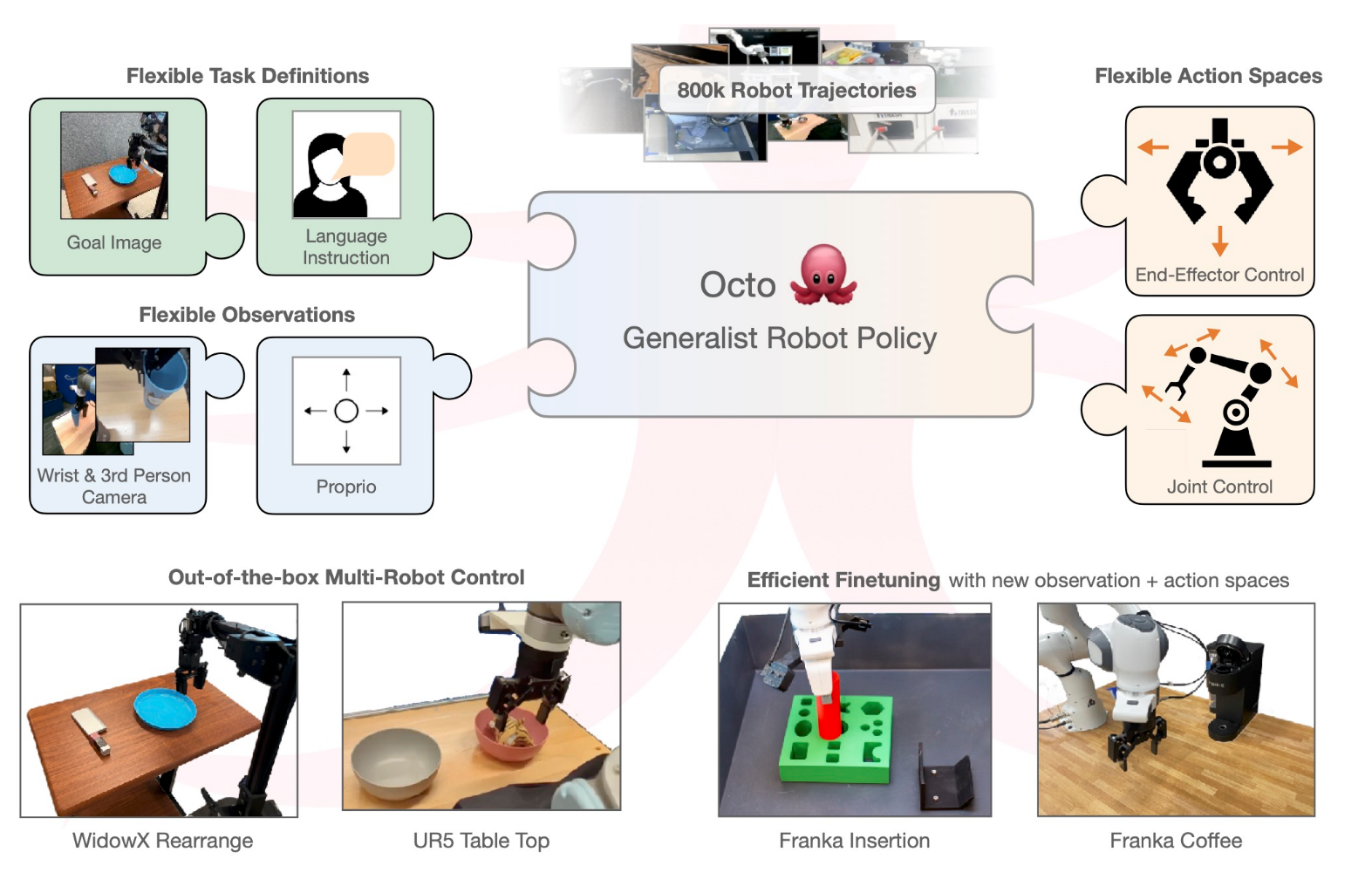

Octo (2023)

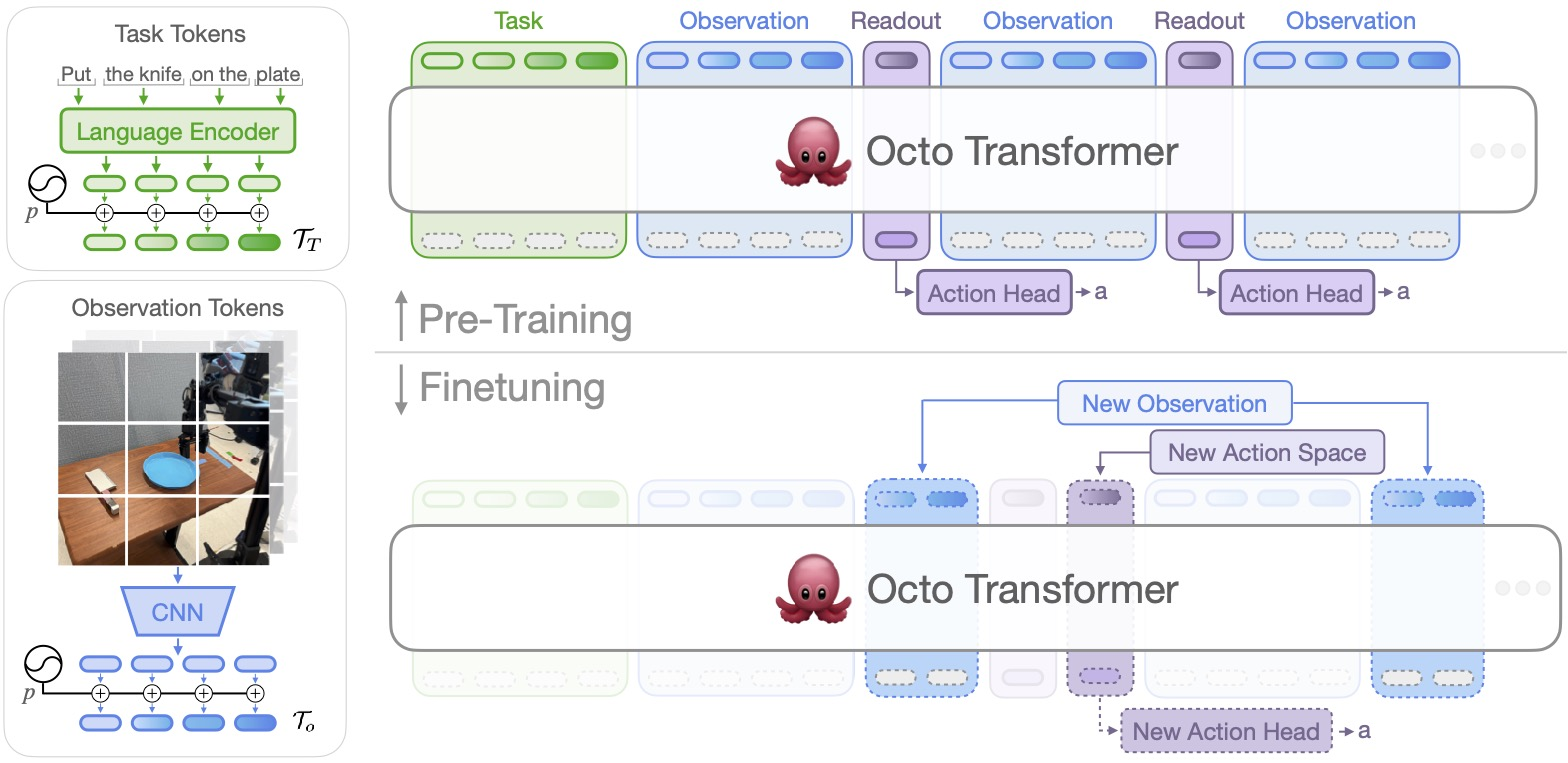

Building on top of the Open-X Embodiments dataset, Octo [16] is a transformer-based diffusion policy, pretrained on $800$k robot episodes. It supports flexible task and observation definitions and can be quickly finetuned to new observation and action spaces. They introduce two initial versions of Octo, Octo-Small ($27$M parameters) and Octo-Base ($93$M parameters).

The design of the Octo model emphasizes flexibility and scale: the model is designed to support a variety of commonly used robots, sensor configurations, and actions, while providing a generic and scalable recipe that can be trained on large amounts of data. Octo supports both natural language instructions and goal images, observation histories, and multi-modal action distributions via diffusion decoding.

Furthermore, Octo was designed specifically to support efficient finetuning to new robot setups, including robots with different actions and different combinations of cameras and proprioceptive information. This design was selected specifically to make Octo a flexible and broadly applicable generalist robotic policy that can be utilized for a variety of downstream robotics applications and research projects.

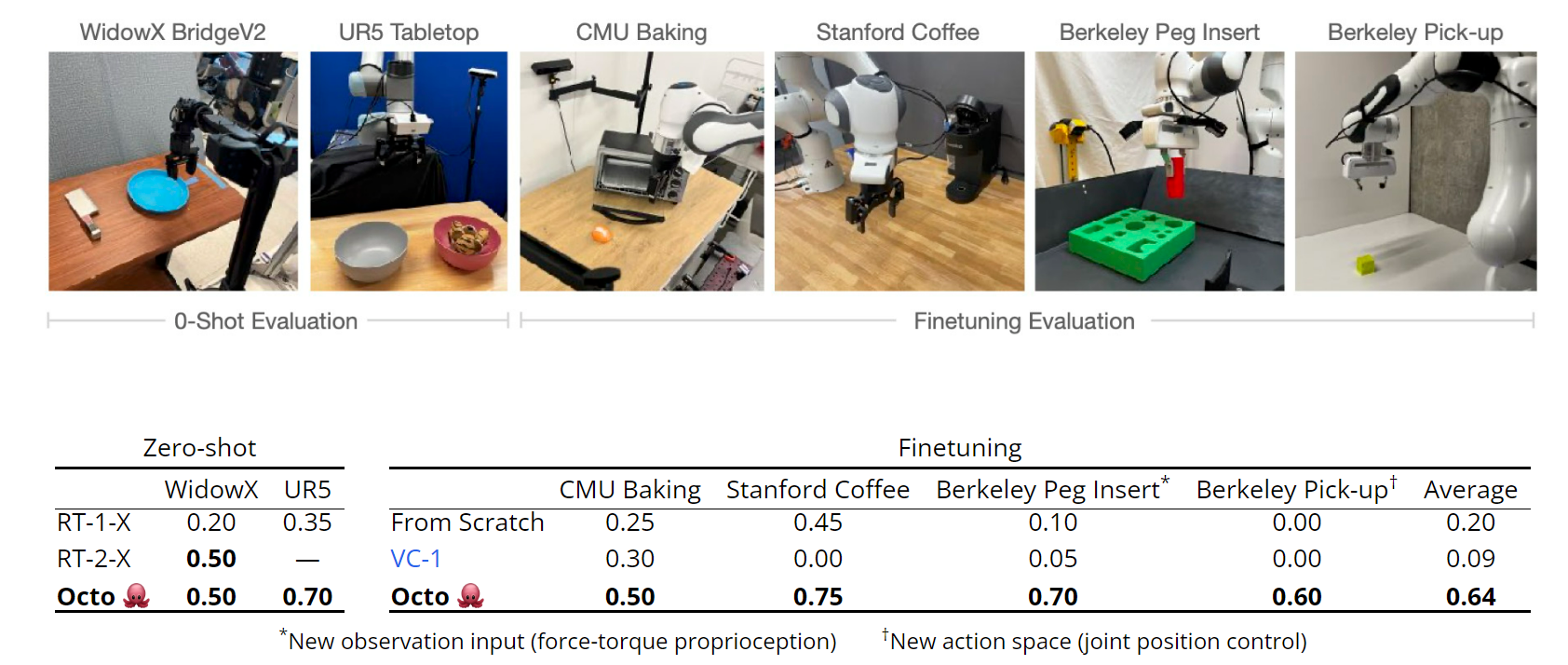

Experiments and Results

Out-of-the-box, Octo can control multiple robots in environments from the pretraining data. When using natural language to specify tasks, it outperforms RT-1-X: the current best, openly available generalist robotic policy. It performs similarly to RT-2-X, a $55$-billion parameter model (which is much larger!).

On the WidowX tasks, Octo achieved even better performance with goal image conditioning: $25$% higher on average. This is likely the case because goal images provide more information about how to achieve the task.

Finally, Octo leads to better policies than starting from scratch or with pretrained weights, with an average success rate improvement of $55$% across the four evaluation tasks. Each task uses ~$100$ target demonstrations.

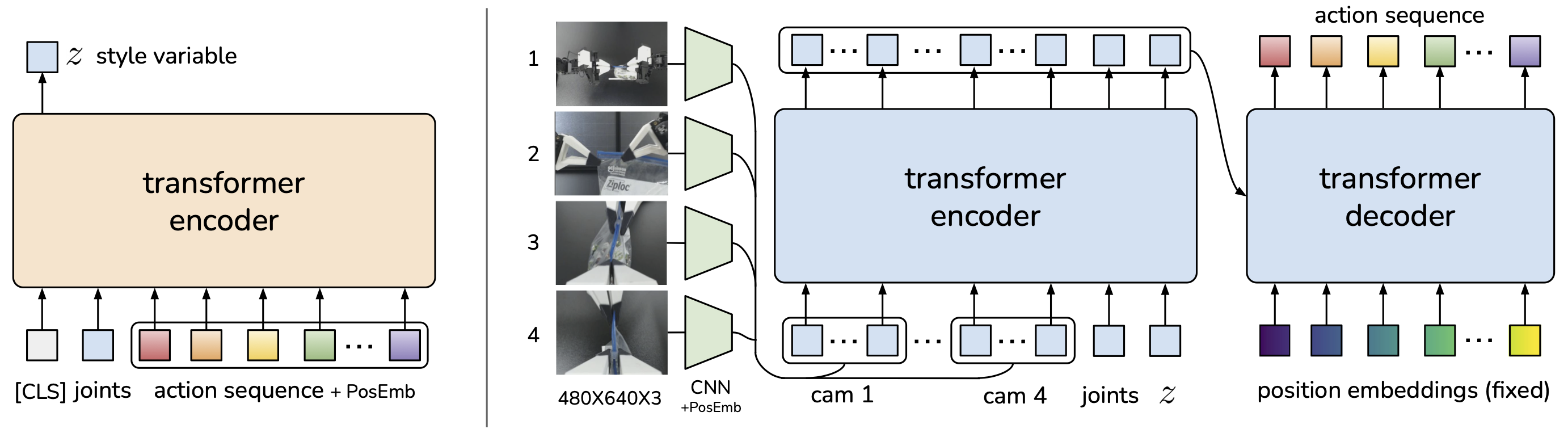

Aloha (2023)

Finally, I wanted to briefly talk about a recent trending work on learning fine-grained bimanual manipulation with low-cost hardware called ALOHA. Since robotics can get expensive very quickly, this paper focusses on enabling low-cost ($$20$k budget for the setup) to do bimanual manipulation using Transformers.

It is capable of teleoperating precise tasks such as threading a zip tie, dynamic tasks such as juggling a ping pong ball, and contact-rich tasks such as assembling the chain in the NIST board.

The paper introduces so-called “Action Chunking with Transformers”, which predicts a sequence of actions (“an action chunk”) instead of a single action like standard behaviour cloning, but do note that the model is still learning to imitate instructions. There is no reinforcement learning or anything to optimize the trajectory.

The ACT policy is trained as the decoder of a Conditional VAE. It synthesizes images from multiple viewpoints, joint positions, and style variable $z$ with a transformer encoder, and predicts a sequence of actions with a transformer decoder. The encoder of CVAE compresses action sequence and joint observation into $z$, the “style” of the action sequence. At test time, the CVAE encoder is discarded and $z$ is simply set to the mean of the prior (i.e. zero).

Experiments and Results

The videos below show real-time rollouts of ACT policies, imitating from $50$ demonstrations for each task. For the four evaluation tasks, ACT obtains 96%, 84%, 64%, 92% success respectively.

In additional experiments they also show that the policy is reactive and robust to previously unseen environmental disturbances instead of just memorizing the training data.

Challenges and Opportunities

There are still plenty of challenges in these fields, and I have made and taken a small list of challenges from some of the papers we discussed:

- How to Leverage or Collect Datasets.

- The broad datasets from vision and language $D$ and the task specific interactive datasets $D_\mathrm{RL}$ can be of distinct modalities and structures. For instance, when $D$ consists of videos, it generally does not contain explicit action labels indicating the cause-effect relationship between different frames, nor does it contain explicit reward labels indicating which videos are better than others, whereas actions and rewards are key components of $D_\mathrm{RL}$.

- How to Structure Environments and Tasks.

- Unlike vision and language where images or texts can serve as a universal task interface, decision making faces environment diversity where different environments operate under distinct state action spaces (e.g., the joint space and continuous controls in MuJoCo are fundamentally different from the image space and discrete actions in Atari), thereby preventing knowledge sharing and generalization.

- Improving Foundation Models.

- Long-context and External Memory.

- Combining multiple foundation models.

- Grounding foundation models in the world.

- Improving Decision Making.

- How to extract desirable behaviour.

- Offline to online.

- Robots with very different sensing and actuation modalities.

- Going beyond behaviour cloning for robotics.

Bibliography

[1] Chen, L., Lu, K., Rajeswaran, A., Lee, K., Grover, A., Laskin, M., … & Mordatch, I. (2021). Decision transformer: Reinforcement learning via sequence modeling. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34, 15084-15097.

[2] Lee, K. H., Nachum, O., Yang, M. S., Lee, L., Freeman, D., Guadarrama, S., … & Mordatch, I. (2022). Multi-game decision transformers. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 27921-27936.

[3] Yang, S., Nachum, O., Du, Y., Wei, J., Abbeel, P., & Schuurmans, D. (2023). Foundation models for decision making: Problems, methods, and opportunities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.04129.

[4] Reed, S., Zolna, K., Parisotto, E., Colmenarejo, S. G., Novikov, A., Barth-Maron, G., … & de Freitas, N. (2022). A generalist agent. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.06175.

[5] Baker, B., Akkaya, I., Zhokov, P., Huizinga, J., Tang, J., Ecoffet, A., … & Clune, J. (2022). Video pretraining (vpt): Learning to act by watching unlabeled online videos. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 24639-24654.

[6] Venuto, D., Yang, S., Abbeel, P., Precup, D., Mordatch, I., & Nachum, O. (2023, July). Multi-environment pretraining enables transfer to action limited datasets. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 35024-35036). PMLR.

[7] Raman, S. S., Cohen, V., Rosen, E., Idrees, I., Paulius, D., & Tellex, S. (2022, November). Planning with large language models via corrective re-prompting. In NeurIPS 2022 Foundation Models for Decision Making Workshop.

[8] Reid, M., Yamada, Y., & Gu, S. S. (2022). Can wikipedia help offline reinforcement learning?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.12122.

[9] Li, S., Puig, X., Paxton, C., Du, Y., Wang, C., Fan, L., … & Zhu, Y. (2022). Pre-trained language models for interactive decision-making. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 31199-31212.

[10] Lu, K., Grover, A., Abbeel, P., & Mordatch, I. (2022, June). Frozen pretrained transformers as universal computation engines. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence (Vol. 36, No. 7, pp. 7628-7636).

[11] Guss, W. H., Castro, M. Y., Devlin, S., Houghton, B., Kuno, N. S., Loomis, C., … & Vinyals, O. (2021). The minerl 2020 competition on sample efficient reinforcement learning using human priors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.11071.

[12] Wang, G., Xie, Y., Jiang, Y., Mandlekar, A., Xiao, C., Zhu, Y., … & Anandkumar, A. (2023). Voyager: An open-ended embodied agent with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.16291.

[13] Zhou, E., Qin, Y., Yin, Z., Huang, Y., Zhang, R., Sheng, L., … & Shao, J. (2024). MineDreamer: Learning to Follow Instructions via Chain-of-Imagination for Simulated-World Control. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.12037.

[14] Padalkar, A., Pooley, A., Jain, A., Bewley, A., Herzog, A., Irpan, A., … & Jain, V. (2023). Open x-embodiment: Robotic learning datasets and rt-x models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.08864.

[15] Brohan, A., Brown, N., Carbajal, J., Chebotar, Y., Chen, X., Choromanski, K., … & Zitkovich, B. (2023). Rt-2: Vision-language-action models transfer web knowledge to robotic control. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.15818.

[16] Team, O. M., Ghosh, D., Walke, H., Pertsch, K., Black, K., Mees, O., … & Levine, S. (2023). Octo: An open-source generalist robot policy.