CS-330 Lecture 5: Few-Shot Learning via Metric Learning

This lecture is part of the CS-330 Deep Multi-Task and Meta Learning course, taught by Chelsea Finn in Fall 2023 at Stanford. The goal of this lecture is to to understand the third form of meta learning: non-parametric few-shot learning. We will also compare the three different methods of meta learning. Finally, we give practical examples of meta learning, in domains such as imitation learning, drug discovery, motion prediction, and language generation!

The goal of this lecture is to understand the third form of meta learning: non-parametric few-shot learning. We will also compare the three different methods of meta learning. Finally, we give practical examples of meta learning, in domains such as imitation learning, drug discovery, motion prediction, and language generation! If you missed the previous lecture, which was about optimization-based meta learning, you can head over here to view it.

As always, since I am still new to this blogging thing, reach out to me if you have any feedback on my writing, the flow of information, or whatever! You can contact me through LinkedIn. ☺

The link to the lecture slides can be found here.

Quick recap

So far, we have discussed two approaches to meta learning: black-box meta learning, and optimization-based meta learning.

-

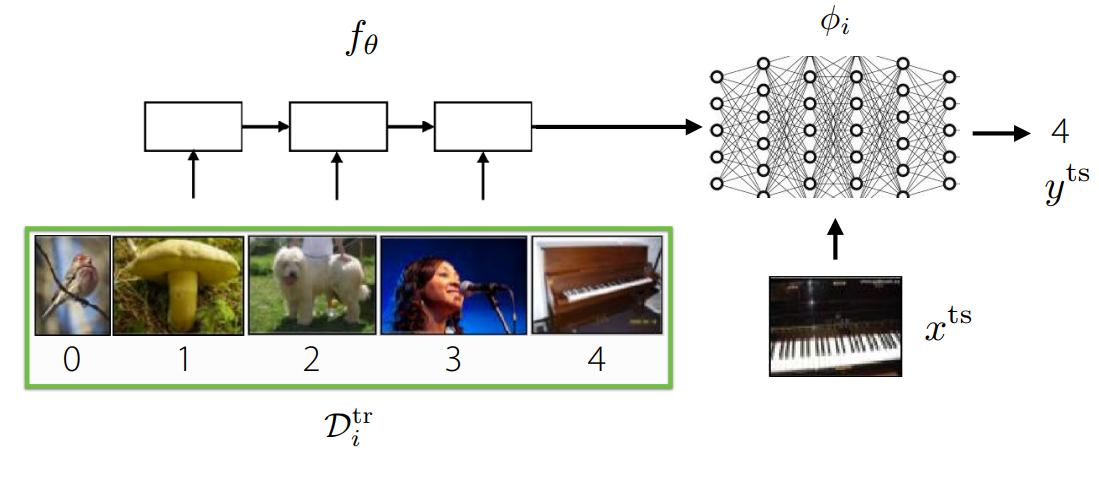

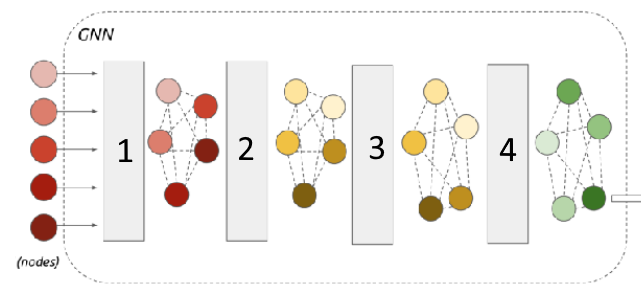

Computation pipeline for black-box meta learning. In black-box meta learning, we attempt to train some sort of meta-model to output task-specific parameters or contextual information, which can then be used by another model to solve that task. We saw that this method is very expressive (e.g. it can model many tasks). However, it also requires solving a challenging optimization problem, which is incredibly data-inefficient.

-

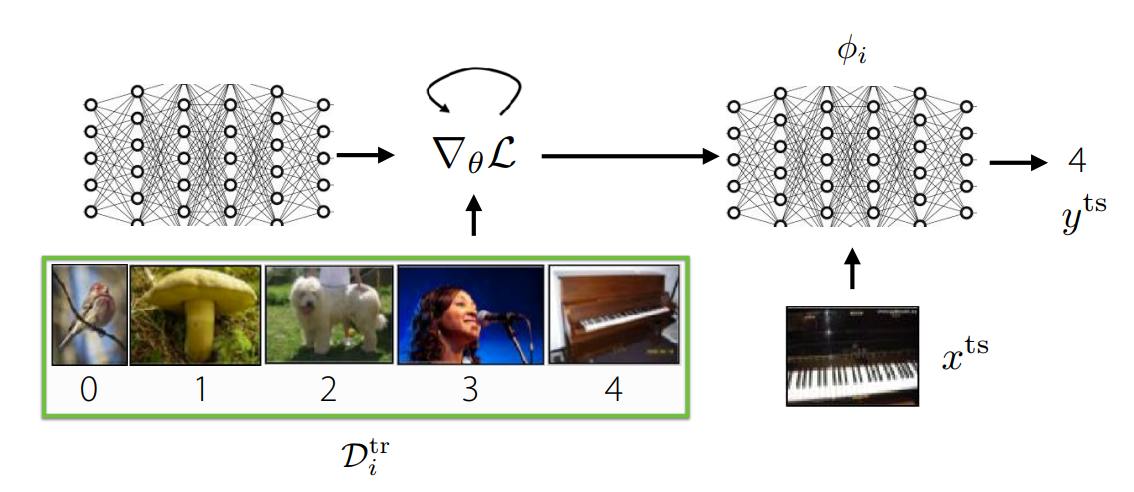

Optimization-based meta learning.

Computation pipeline for optimization-based meta learning. We then talked about optimization-based meta learning, which embeds an optimization process within the inner learning process. This way, you can learn to find parameters to a model such that optimizing these parameters to specific tasks is as effective and efficient as possible. We saw that model-agnostic meta learning preserves expressiveness over tasks, but it remains memory-intensive, and requires solving a second-order optimization problem.

Non-parametric few-shot learning

In the previous two approaches to meta learning, we only talked about parametric methods

One benefit of non-parametric methods is that they generally work well in low data regimes, making it a great opportunity for few-shot learning problems at meta-test time. Nevertheless, during meta-training time, we would still like to use a parametric learner to exploit the potentially large amounts of data.

The key idea behind non-parametric approaches is to compare the task-specific test data to the data in the train dataset. We will continue using the example of the few-shot image classification problem, as in the previous posts. If you want to compare images to each other, you need to come up with a certain metric to do so.

The simplest idea might be to utilize the $\ell_2$-distance. Unfortunately, it is not that simple. If you look at the figure above, you can see the image of a woman on the right and two augmented versions on the left. When you calculate the $\ell_2$-distance between the original image and the augmented image, the distance between the blurry image and the original one is smaller than the other distortion, even though this may resemble the original image more. For this problem, you could use a different metric, such as a perceptual loss function

In this post, we will discuss three different ways of doing metric learning, starting with the easiest and building our way up. Firstly, we will talk about the most basic model: Siamese networks.

Siamese networks

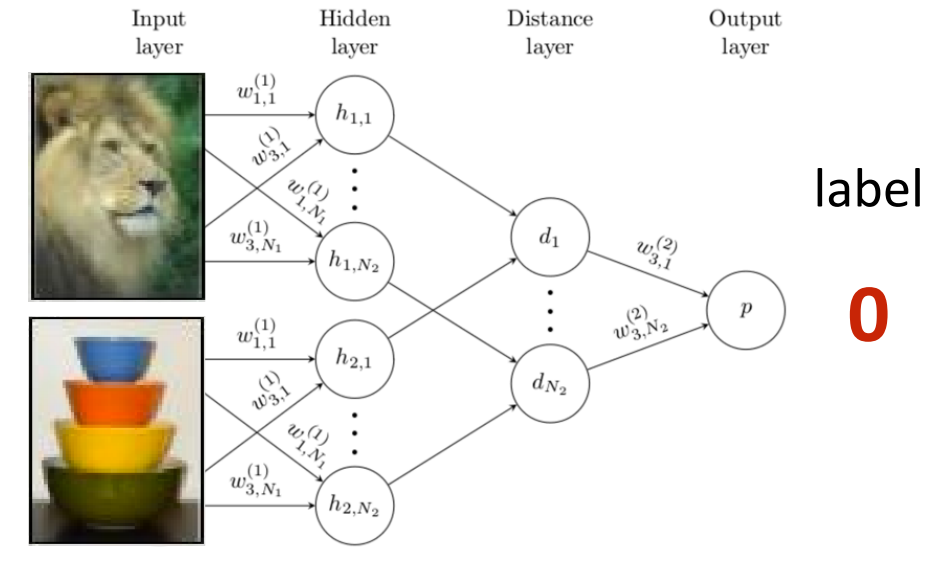

With a Siamese network, the goal is to learn whether two images belong to the same class or not. The input to the model is two images, and it outputs whether it thinks they belong to the same class. However, the penultimate activations correspond to a learned distance metric between these images. At meta-train time, you are simply trying to minimize the binary cross-entropy loss.

At meta-test time, you need to compare the test image $x_\mathrm{test}$ against every image in the test-time training dataset $\mathcal{D}^\mathrm{tr}$, and then select the class of the image that has the highest probability. This corresponds to the equation below (for simplicity of the equation, we assume that only one sample will have $f_\theta(x_j^\mathrm{test}, x_k) > 0.5$). Furthermore, $1$ corresponds to the indicator function.

\[\hat{y}_j^\mathrm{test} := \sum_{(x_k, y_k) \sim \mathcal{D}^\mathrm{tr}} 1(f_\theta(x_j^\mathrm{test}, x_k) > 0.5)y_k\;.\]With this method, there is a mismatch between meta-training and meta-testing. During meta-training, you are solving a binary classification problem, whilst during meta-testing, you are solving an $N$-way classification problem. You cannot phrase meta-training in the same way, since the indicator function $1$ makes $\hat{y}_j^\mathrm{test}$ non-differentiable. We will try to resolve this by introducing matching networks.

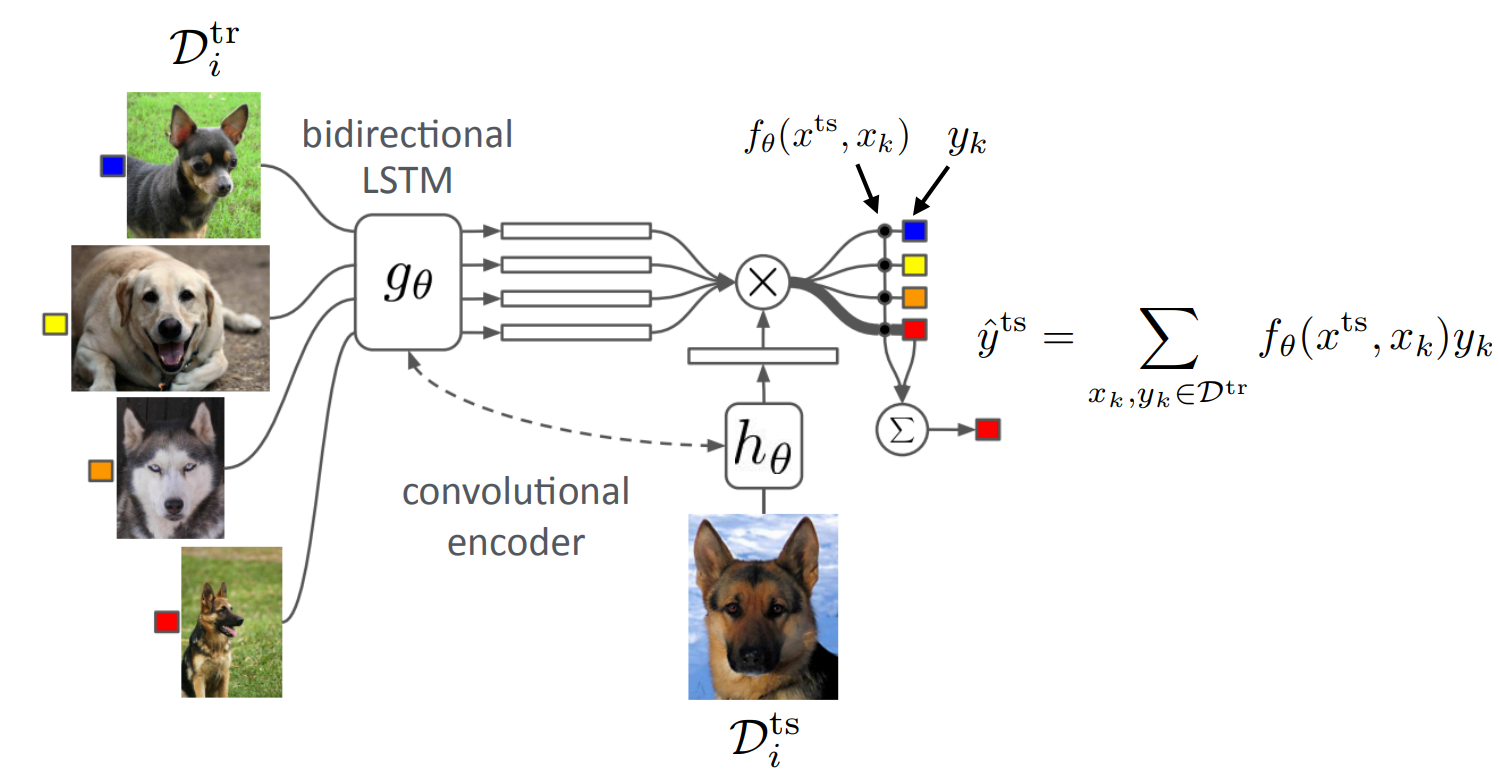

Matching networks

In the previous equation above, we saw that at meta-test time, we use the class of the most similar training example as the estimate of the test sample. In order to get rid of the mismatch between meta-training and meta-testing, we can rephrase the meta-testing objective similarly to what we saw. Let’s say we instead modify the procedure to use a mix of class predictions as a class estimate. This would result in the equation below.

\[\hat{y}_j^\mathrm{test} := \sum_{(x_k, y_k) \sim \mathcal{D}^\mathrm{tr}} f_\theta(x_j^\mathrm{test}, x_k)y_k\;.\]At meta-train time, we can now use the same objective, and backpropagate through the cross-entropy loss $y_j^\mathrm{test} \log(\hat{y}_j^\mathrm{test}) + (1-y_j^\mathrm{test})\log(1-\hat{y}_j^\mathrm{test})$. This way, both meta-training and meta-testing are aligned with the same procedure. Our meta-training process would become:

- Sample task $\mathcal{T}_i$.

- Sample two images per class, giving $D_i^\mathrm{tr}, D_i^\mathrm{test}$.

-

Compute $\hat{y}^\mathrm{test} = \sum_{(x_k, y_k) \sim \mathcal{D}^\mathrm{tr}_i} f_\theta(x^\mathrm{test}, x_k)y_k$.

- Backpropagate the loss with respect to $\theta$.

This idea corresponds to so-called “matching networks”

Let’s stand still with what we’re doing for a second and think about how this approach is non-parametric. If we recall from parametric models, we would always compute task-specific parameters $\phi_i \leftarrow f_\theta(\mathcal{D}_i^\mathrm{tr})$. However, now have integrated the parameters $\phi$ out by computing $\hat{y}_j^\mathrm{test} := \sum_{(x_k, y_k) \sim \mathcal{D}^\mathrm{tr}} f_\theta(x_j^\mathrm{test}, x_k)y_k$ directly by comparing to the training dataset, making it non-parametric.

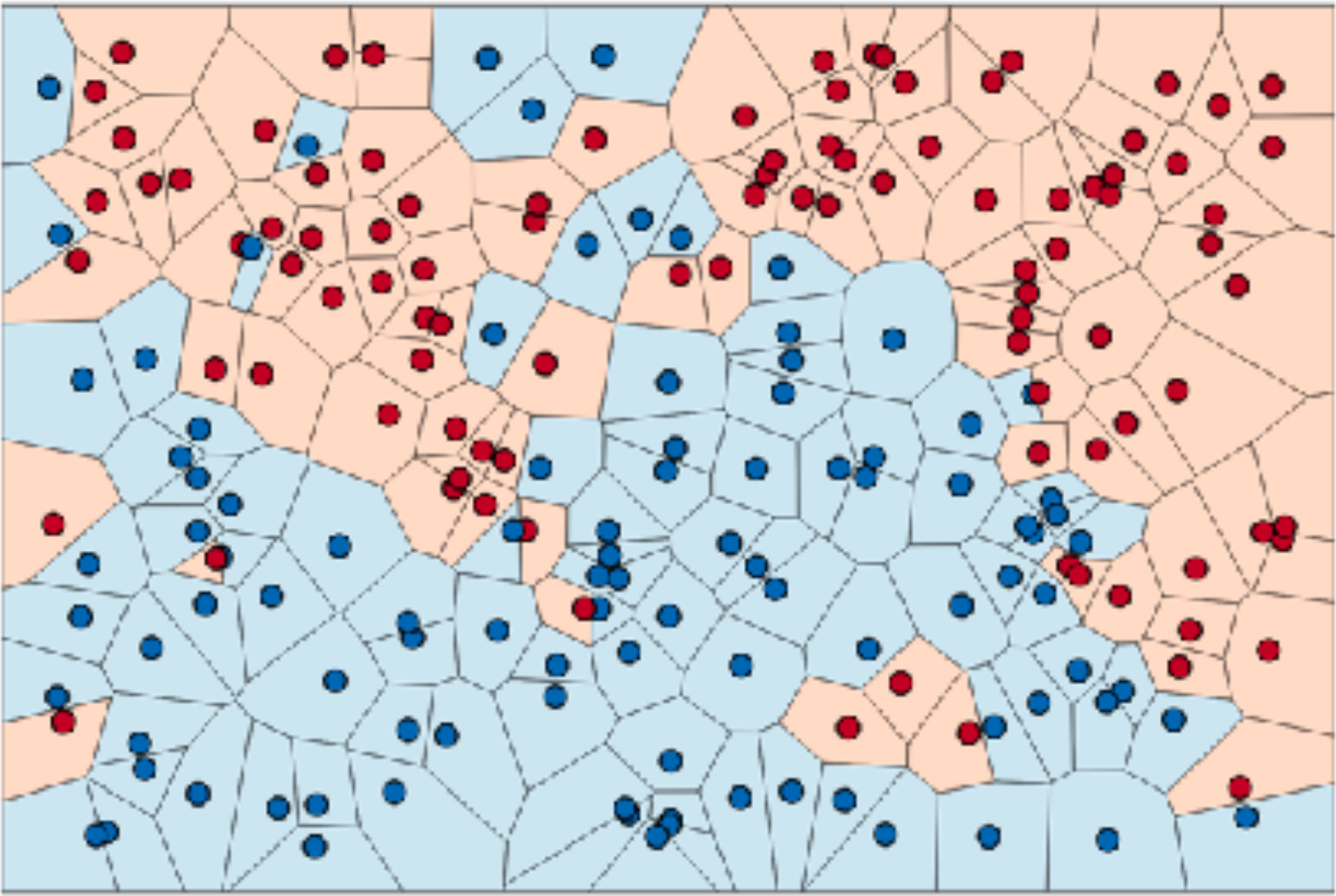

In the meta-training procedure described, we would sample two images per class. But what would happen if we sampled more than two images (ignoring potential class imbalance)? Well, with matching networks, each sample of each class is evaluated independently with $f_\theta(x_j^\mathrm{test}, x_k)$ instead of together. This could lead to strange results if the majority of a class has a low confidence but there is an outlier with a high confidence, overpowering the correct label. This can be depicted in the right figure. Imagine if you want to predict the label of the black square. The dot-product score with the red sample might be so high that it overpowers the other samples, even though it is more likely part of the blue class. We will try to resolve this by calculating prototypical embeddings that average class information.

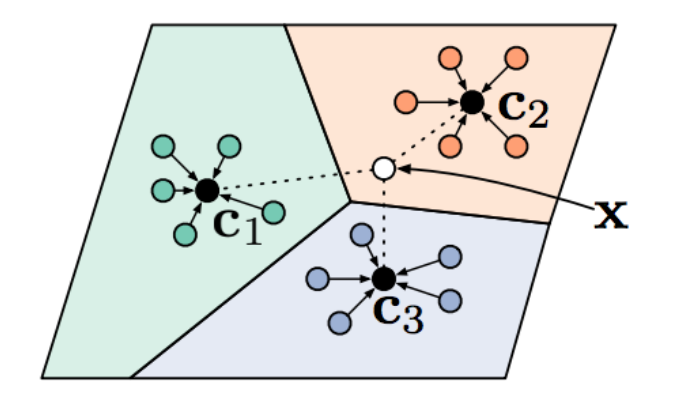

Prototypical models

Prototypical models

As opposed to the matching networks, we are now using the same embedding function $f_\theta$ for both the training and testing datapoints.

More advanced models

The models that we talked about today are already quite expressive for non-parametric meta learning, but they all do some form of embedding followed by nearest-neighbours. However, sometimes you might need to reason about more complex relationships between datapoints. Let’s briefly discuss a few more recent works that approach this problem.

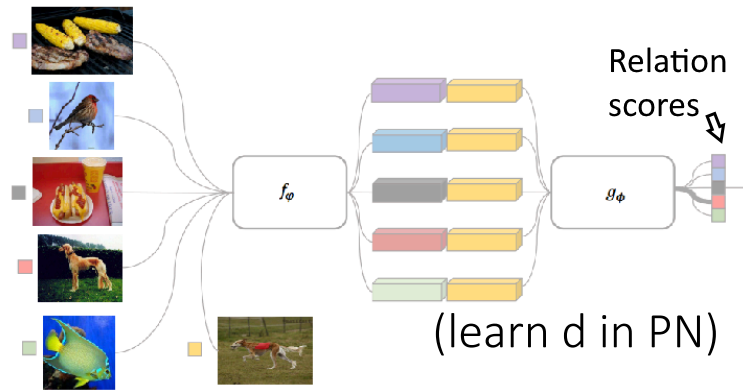

- Relation networks

.

The idea is to learn non-linear relation modules on the embedding. They first embed the images and then compute this relation score, which corresponds to the distance function $d$ that we saw with prototypical models.

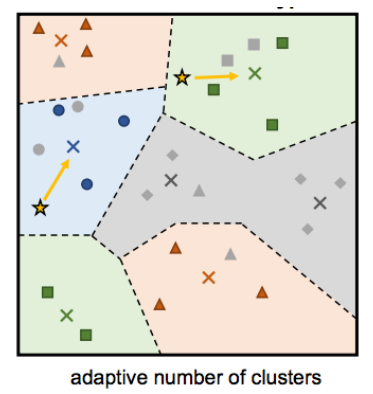

- Infinite mixture of prototypes

.

The idea is to learn an infinite mixture of prototypes, which is useful when classes are not easy to cluster nicely. For example, some breeds of cats might look similar to dogs, which would not be good when averaging class embeddings. In this case, we can have multiple prototypes per class.

- Graph neural networks

.

The idea is to do message passing on the embeddings instead of doing something as simple as nearest neighbours. This way, you can figure out relationships between different examples (i.e. by learning edge weights), and do more complex aggregation.

Properties of meta-learning algorithms

Now that we have seen all three different types of meta learning algorithms, we can compare each approach to see which problems might benefit from which approach. Let’s first quickly summarize all approaches.

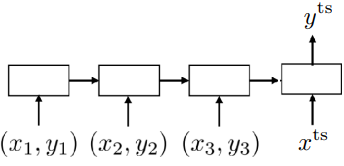

Black-box meta learning.

$y^\mathrm{ts} = f_\theta(\mathcal{D}_i^\mathrm{tr}, x^\mathrm{ts})$.

Optimization-based meta learning.

$y^\mathrm{ts} = f_\mathrm{MAML}(\mathcal{D}_i^\mathrm{tr}, x^\mathrm{ts}) = f_{\phi_i}(x^\mathrm{ts})$, where $\phi_i = \theta - \alpha \nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta, \mathcal{D}^\mathrm{tr})$.

Non-parametric meta learning.

$y^\mathrm{ts} = f_\mathrm{PN}(\mathcal{D}_i^\mathrm{tr}, x^\mathrm{ts}) = \mathrm{softmax}(-d(f_\theta(x^\mathrm{ts}), c_n))$, where $c_n = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{(x,y)\in\mathcal{D}_i^\mathrm{tr}} 1(y_k=n)f_\theta(x_k)$.

As you can see, all these methods share this perspective of a computational graph that we discussed in earlier posts. You can easily mix-and-match different components of these computation graphs. Below are some examples of paper that try this:

- Gradient descent on relation network embeddings.

- Both condition on data and run gradient descent

. - Model-agnostic meta learning, but initialize last layer as a prototype network during meta-training

.

Let’s make a table of the benefits and downsides of each method that we have discussed up to this point in the series:

| Black-box | Optimization-based | Non-parametric |

|---|---|---|

| [+] Complete expressive power | [~] Expressive for very deep models (in a supervised learning setting) | [+] Expressive for most architectures |

| [-] Not consistent | [+] Consistent, reduces to gradient descent | [~] Consistent under certain conditions |

| [+] Easy to combine with a variety of learning problems | [+] Positive inductive bias at the start of meta learning, handles varying and large number of classes well | [+] Entirely feedforward, computationally fast and easy to optimize |

| [-] Challenging optimization problem (no inductive bias at initialization) | [-] Second-order optimization problem | [-] Harder to generalize for varying number of classes |

| [-] Often data-inefficient | [-] Compute- and memory-intensive | [-] So far limited to classification |

- Expressive power: The ability of $f$ to model a range of learning procedures.

- Consistency: Learned learning procedure will monotonically improve with more data

- Uncertainty awareness: Ability to reason about ambiguity during learning.

We have not yet discussed the uncertainty awareness of methods, but it plays an important role in active learning, calibrated uncertainty, reinforcement learning, and principled Bayes approaches. We will discuss this later on in the series!

Examples of meta learning in practice

In this section, we will very briefly talk about 6 different problem settings where meta learning has been used, some of which we have already seen in previous posts. This should give you a good idea of some different applications, and show you that it can be utilized in many different domains.

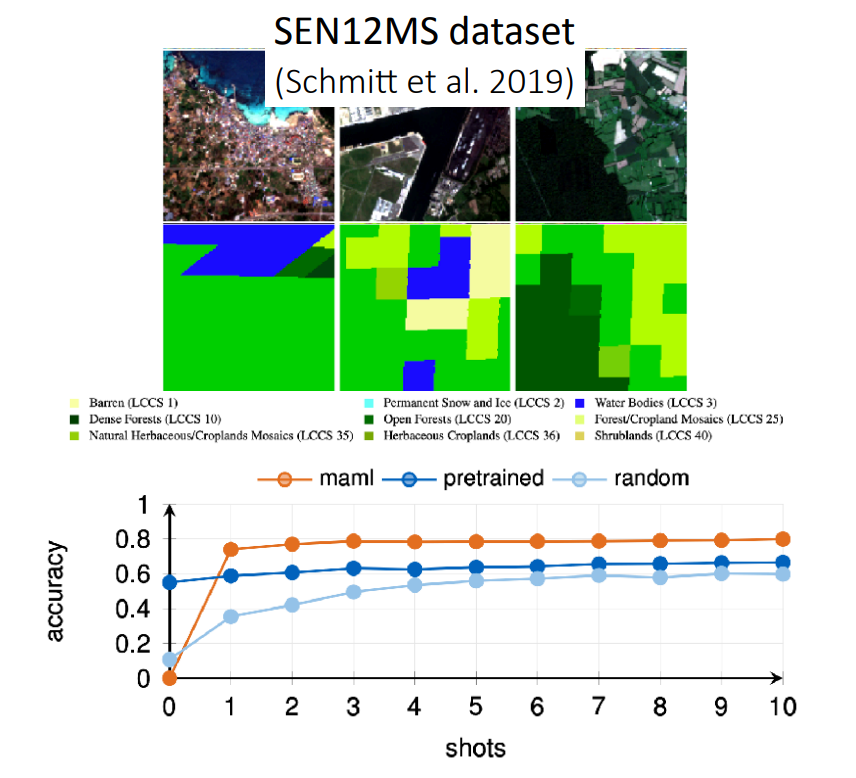

Land-cover classification

The goal of this paper

Model: Optimization-based (model-agnostic meta learning)

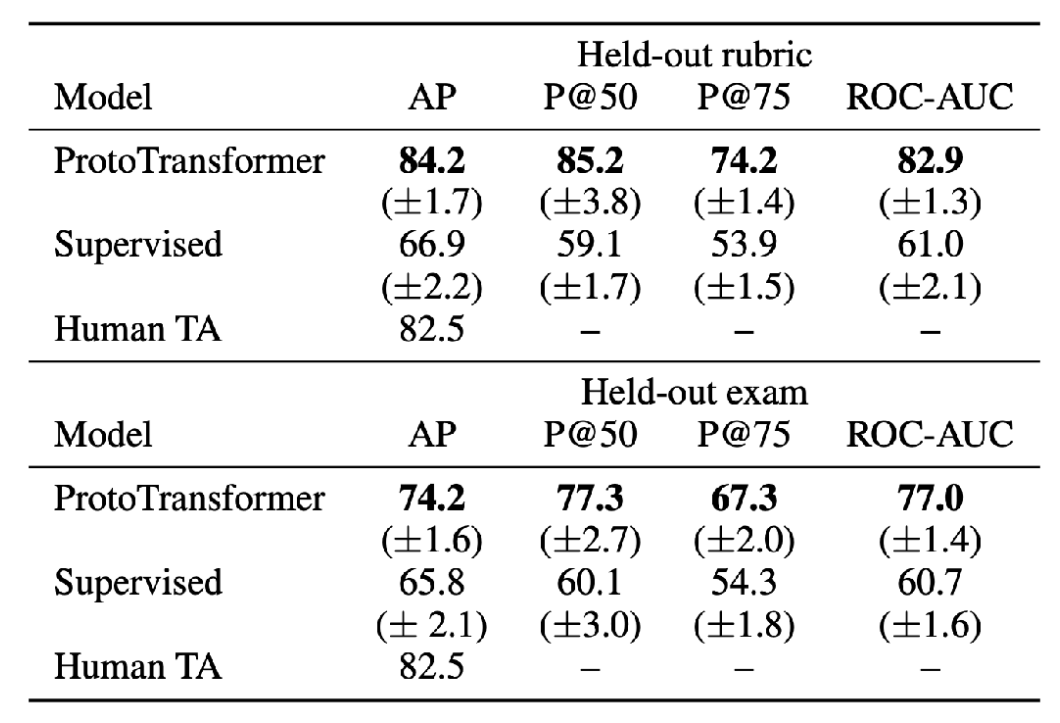

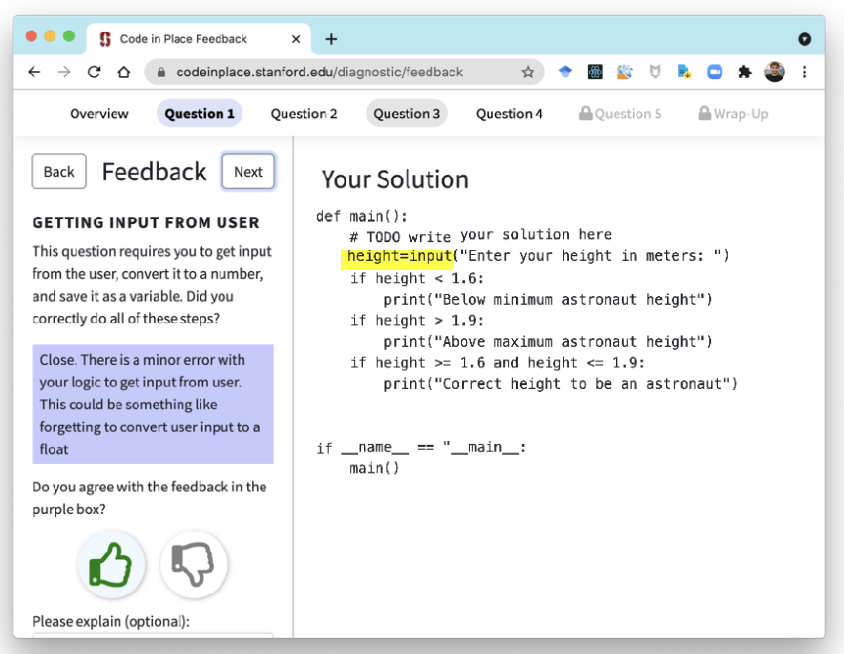

Student feedback generation

The goal of this paper

Supervised baseline: Train a classifier per task, using same pre-trained CodeBERT

Outperforms supervised learning by 8-17%, and more accurate than human TA on held-out rubric! However, there is room for improvement on a held-out exam.

Model: Non-parametric (prototypical network with pre-trained Transformer, task information, and side information).

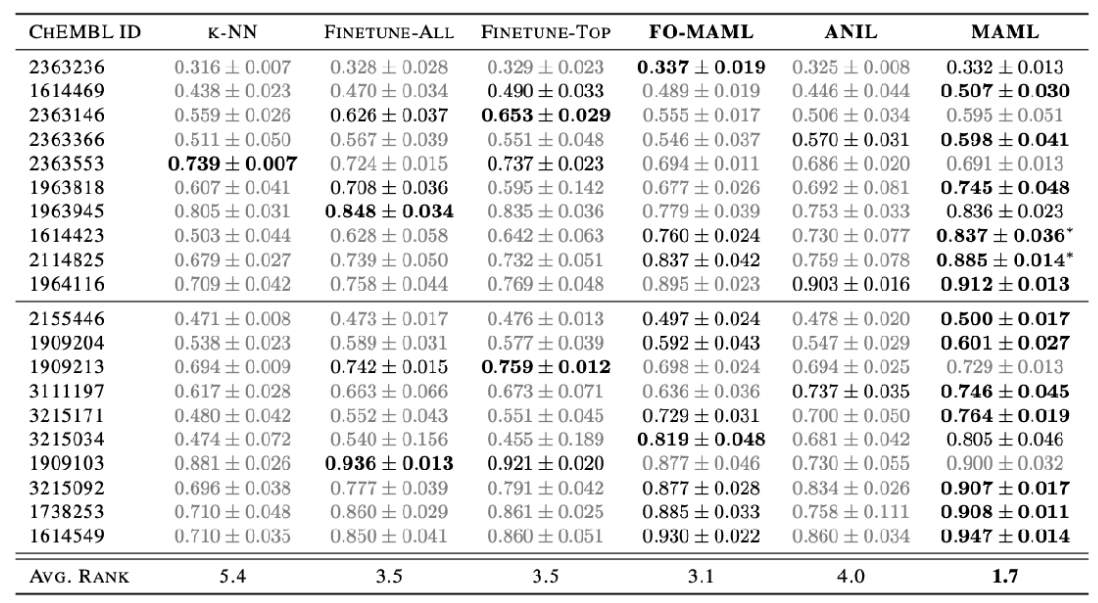

Low-resource molecular property prediction

The goal of this paper

Model: Optimization-based MAML, first-order MAML, and an ANIL Gated graph neural net base model.

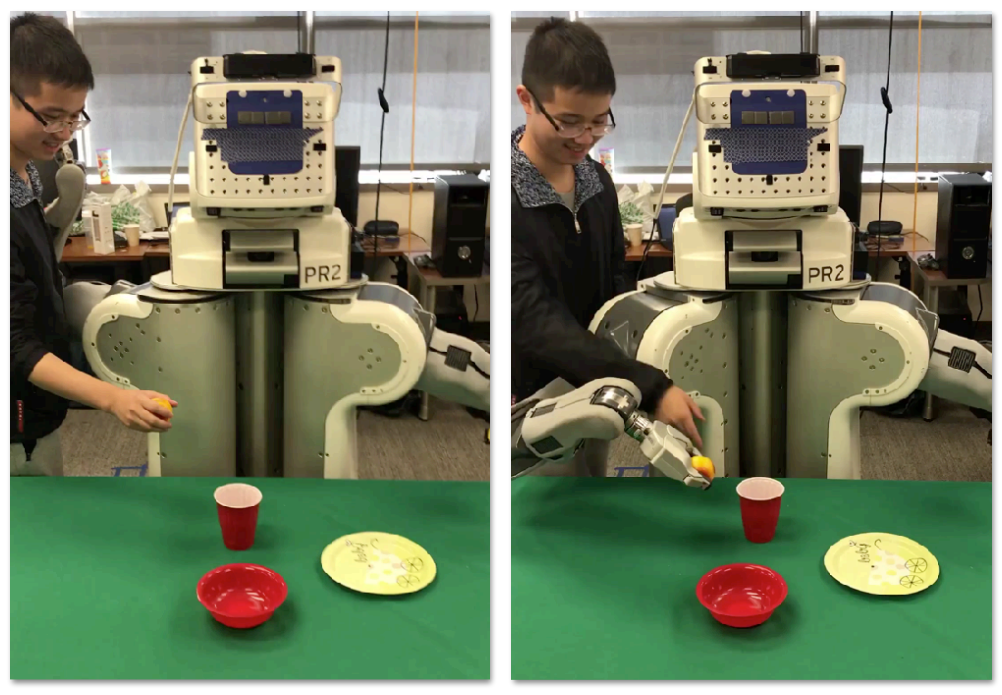

One-shot imitation learning

The goal of this paper

Note: See that they training and testing datasets do not need to be sampled independently from the overall dataset for meta learning to work!

Model: Model-agnostic meta learning with learned inner loss function.

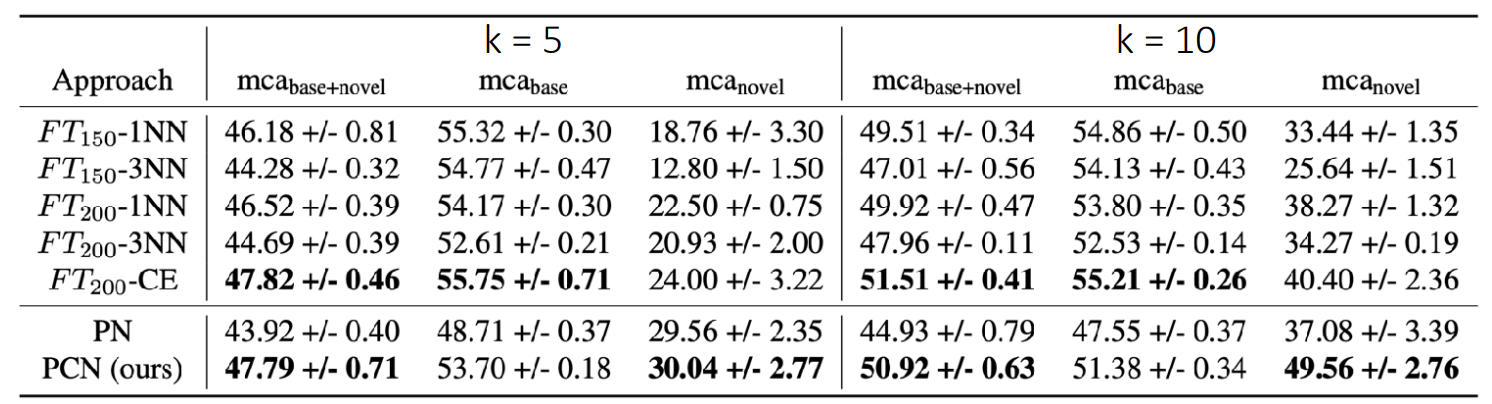

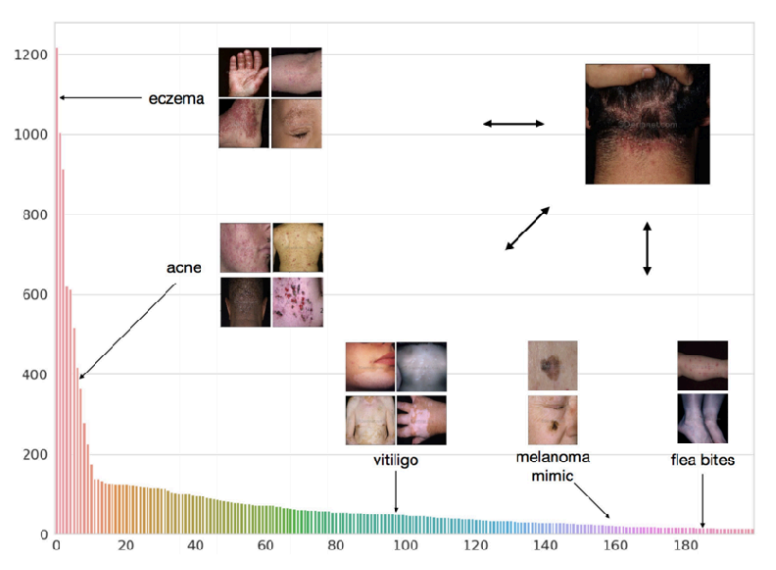

Dermatological image classification

The goal of this paper

Model: Non-parametric prototype networks with multiple prototypes per class using clustering objective.

Results show that the clustering prototype networks perform better than normal ones and competitive against a ResNet model that is pre-trained on ImageNet and fine-tuned on 200 classes with balancing. This is a very strong baseline with access to more info during training, and it requires re-training for new classes.

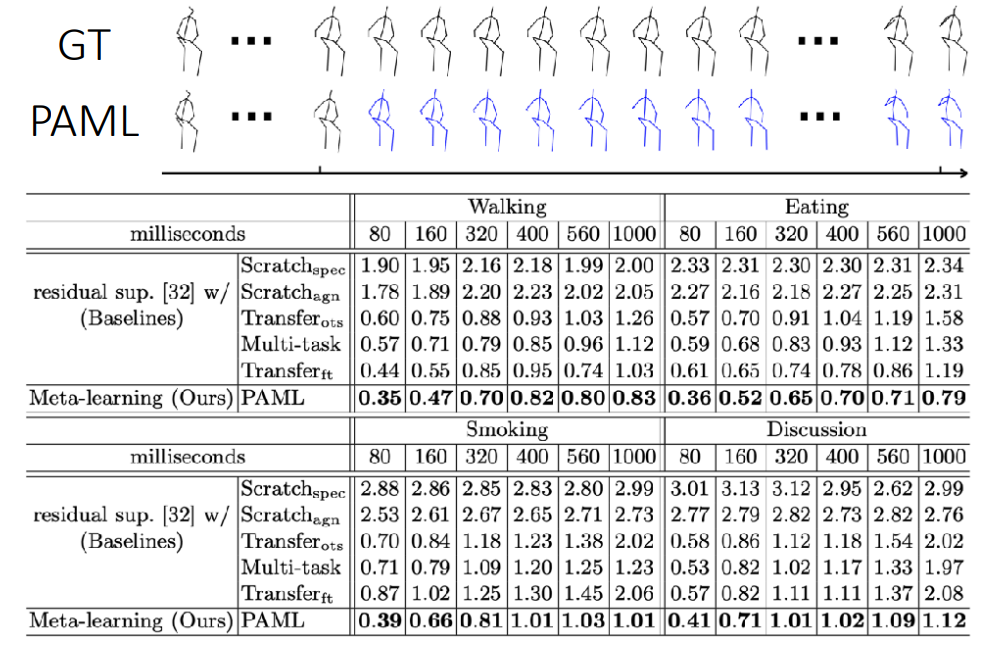

Few-shot human motion prediction

The goal of this paper

Note: See that they training and testing datasets do not need to be sampled independently from the overall dataset for meta learning to work!

Model: Optimization-based/black-box hybrid, MAML with additional learned update rule and a recurrent neural net base model.