A Deep Dive into Behavioural Foundation Models with Meta Motivo

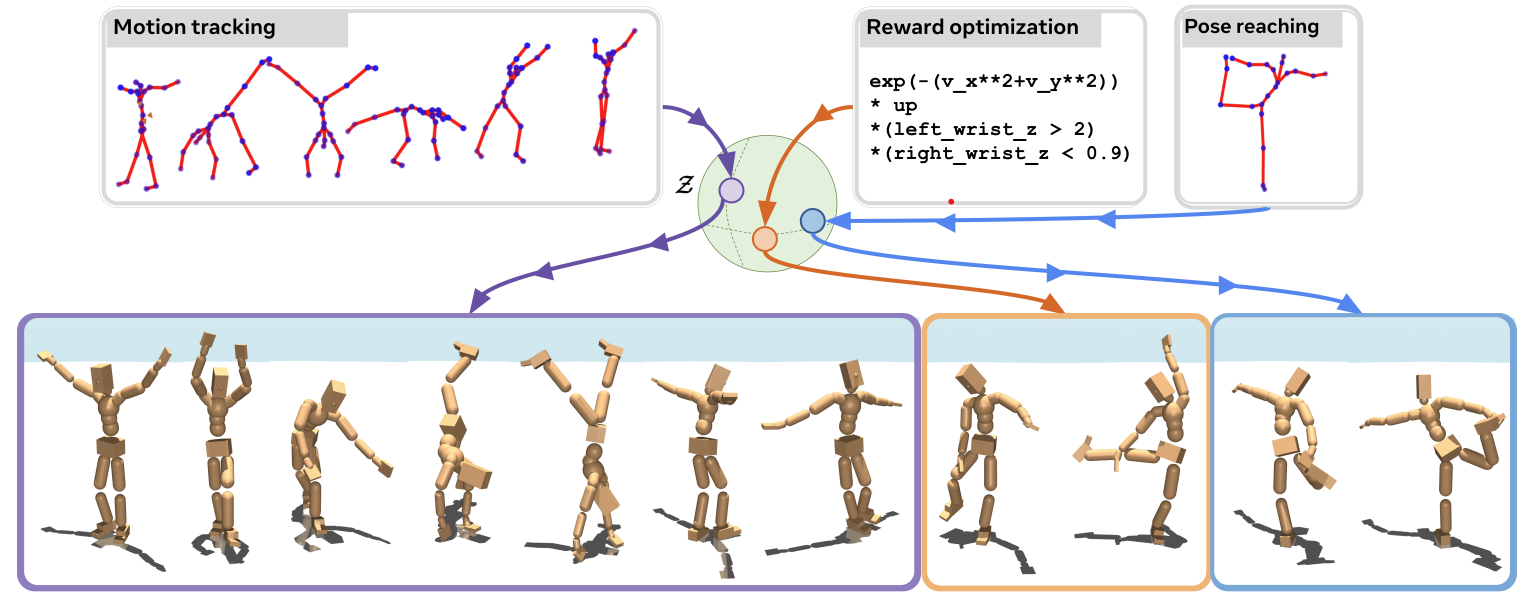

In this post, I aim to explore the evolution of behavioral foundation models (BFMs) and their role in reinforcement learning, robotics, and zero-shot policy adaptation. We will begin by understanding Forward-Backward Representations (FB) and how they enable learning compact, reusable representations of environments. Then, we will examine how Meta Motivo, the first behavioral foundation model for humanoid control, leverages FB representations and imitation learning to perform whole-body control tasks with zero-shot generalization. Along the way, we will connect these ideas to broader trends in unsupervised RL, successor measures, and policy optimization, making the case for why BFMs are a promising direction for future AI systems that generalize across diverse tasks without retraining.

TODO: Address figure credits!!

Disclaimer: The figures presented in this blog are not created by me. I have simply copied them from the corresponding papers, and they will be credited appropriately throughout the post.

Reinforcement learning (RL) has traditionally relied on training separate policies for each task, but this approach doesn’t scale well—every new task requires costly retraining. The goal of behavioral foundation models (BFMs) is to develop general-purpose policies that can quickly adapt to new tasks without starting from scratch. Meta Motivo, one of the first BFMs for humanoid control, achieves this by learning a structured representation of behaviors that allows for zero-shot generalization across diverse movement tasks.

But how do we learn such representations? At the heart of this approach is the successor measure, a mathematical tool that describes how an agent moves through its environment under a given policy. Instead of storing individual trajectories, the successor measure provides a compressed, reusable representation of future state distributions, making it possible to efficiently transfer knowledge across tasks.

To approximate these measures in a structured way, we introduce Forward-Backward (FB) Representations, a framework that breaks down future state predictions into two components:

- A forward embedding that captures how actions influence future states.

- A backward embedding that captures how states are reached from past actions.

Once we have this framework, we’ll explore how it enables fast imitation learning, allowing agents to learn from demonstrations efficiently. Finally, we’ll connect all these principles and introduce Meta Motivo’s optimization pipeline, showing how it unifies these ideas to enable rapid adaptation to new tasks.

Note that, in this post, I will assume that the reader is familiar with the reinforcement learning framework, since I believe that the topic of this blog requires quite some background knowledge, mainly about the general framework and bellman equations. This post will also be quite math-heavy and proof-oriented, as we will derive key equations and discuss the theoretical foundations behind these methods. However, if anything is unclear, feel free to reach out to me for any questions or remarks!

The Successor Measure: Predicting State Occupancy in RL

One of the most fundamental problems in reinforcement learning (RL) is understanding what happens after taking an action. If an agent takes an action in a given state, where will it go next? More importantly, what is the long-term impact of that action?

Traditionally, RL algorithms try to answer these questions using value functions, which estimate the expected reward an agent will collect in the future. But what if we didn’t care about rewards at all and simply wanted to understand the structure of an environment? This is where the successor measure comes in.

The successor measure is a way to describe how an agent moves through the state space over time. It captures the probability of visiting different states in the future, weighted by how soon they are reached. Once we have this information, we can quickly adapt to new tasks without needing to relearn everything from scratch.

In this section, we’ll build up the formal definition of the successor measure, derive its key properties, and explain why it is a powerful tool for learning general representations of environments.

Motivation: Why Do We Need the Successor Measure?

Let’s say we have an RL agent navigating a maze. At every step, it moves based on a policy $\pi$. If we ask:

- “Which states will this agent visit most often?”

- “How likely is it to reach a particular goal?”

- “How much time will it spend in different areas of the maze?”

the successor measure gives us a precise way to answer these questions.

Instead of memorizing specific paths through the maze, we want to learn a generalized understanding of how the agent moves. This allows us to transfer knowledge between different tasks. If we later change the goal of the agent (e.g., moving from one exit to another), we don’t need to start from scratch—we can simply re-use the successor measure to quickly compute the best policy.

The key insight here is that an agent’s movement pattern depends only on the environment dynamics and its policy, not on the specific reward function. This means that if we can learn a good representation of movement dynamics, we can adapt to new tasks much faster. We will show this later in this section.

Formal Definition of the Successor Measure

Mathematically, the successor measure tracks how much time an agent spends in different states when following a given policy $\pi$.

For a reward-free Markov Decision Process (MDP) $\mathcal{M} = \left(\mathcal{S}, \mathcal{A}, P, \gamma\right)$, the successor measure is defined as follows. Given a state $s \in \mathcal{S}$ and an action $a \in \mathcal{A}$, the successor measure of a set $X \subseteq \mathcal{S}$ is:

\[M^\pi(X \vert s, a) := \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t \mathrm{Pr}(s_{t+1} \in X \vert s, a, \pi)\;.\]This measures the discounted probability that the agent will visit any state in $X$ at some future time step.

Let’s break this down piece by piece:

- $X$ is a set of states that we are interested in.

- $\mathrm{Pr}(s_{t+1} \in X \vert s, a, \pi)$ is the probability that, after $t$ steps, the agent is in $X$, given that it started in $s$ and took action $a$.

- $\gamma^t$ is the discount factor ($0 < \gamma < 1$) that reduces the weight of distant future states, making states which are visited sooner more important.

If $X$ contains just a single state $s^\prime$, then $M^\pi(\{s^\prime\} \vert s, a)$ tells us how much discounted probability mass is assigned to $s^\prime$ in the future. This represents the total discounted probability of visiting $s^\prime$ at any future time step. In other words, it is a measure of occupancy probability rather than raw visit counts.

For the people familiar with measure theory, you can show that $M^\pi(\cdot \vert s, a)$ is a probability measure, meaning it assigns a value to any subset $X \subseteq \mathcal{S}$ in a way that satisfies the properties of a measure:

- Non-negativity: $\forall X \subseteq \mathcal{S} \quad M^\pi(X \vert s, a) \geq 0$.

- Countable additivity: For disjoint sets $X_1, X_2, \dots$, we have $M^\pi(\cup_i X_i \vert s, a) = \sum_i M^\pi(X_i \vert s, a)$.

- Normalization: if $X = \mathcal{S}$, then $M^\pi(S \vert s, a)$ represents the total discounted probability mass distributed over all future states.

The Successor Measure as a Bellman Equation

One of the most useful properties of the successor measure is that it satisfies a recursive relationship, similar to the Bellman equation used in reinforcement learning. Specifically, the successor measure follows:

\[M^\pi(X \vert s, a) = \mathrm{Pr}(X \vert s, a) + \gamma \mathbb{E}_{s^\prime \sim P(\cdot \vert s, a), a^\prime \sim \pi(\cdot \vert s^\prime)}\left[M^\pi(X \vert s^\prime, a^\prime)\right]\;.\]This equation tells us that the total expected future occupancy of $X$ can be broken into two parts:

- Immediate transitions: The probability of moving directly into $X$ in the next step, given by $P(X \vert s,a)$.

- Future discounted occupancy: The expected future measure $M^\pi(X \vert s^\prime, a^\prime)$, weighted by $\gamma$ and averaged over the next states $s^\prime$ and actions $a^\prime$.

This equation is extremely powerful because, like the Bellman equations, it lets us compute $M^\pi$ recursively instead of summing over infinite time steps. This forms the foundation for the loss function used in Meta Motivo’s optimization pipeline, which will be discussed in TODO ADD SECTION!

For people interested in the proof of this equality, we will prove it in the box below:

Proof: By definition, we have $$M^\pi(X \vert s, a) = \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t \mathrm{Pr}(s_{t+1} \in X \vert s, a, \pi)\;.$$

Splitting the sum into the first step ($t = 0$) and all later steps ($t \geq 1$), we get $$M^\pi(X \vert s, a) = \mathrm{Pr}(s_1 \in X \vert s, a) + \sum_{t=1}^\infty \gamma^t \mathrm{Pr}(s_{t+1} \in X \vert s, a, \pi)\;.$$ where we notice that $\mathrm{Pr}(s_1 \in X \vert s, a) = \mathrm{Pr}(X \vert s, a)$.

By marginalizing over $s^\prime$ and $a^\prime$ and using the law of total probability, we can rewrite the latter part of the equation as $$\mathrm{Pr}(s_{t+1} \in X \vert s, a, \pi) = \sum_{s^\prime}P(s^\prime\vert s, a)\sum_{a^\prime}\pi(a^\prime \vert s^\prime)\mathrm{Pr}(s_{t+1} \in X \vert s^\prime, a^\prime, \pi)\;.$$

Finally, we notice that this is an expectation over $s^\prime$ and $a^\prime$, thus we can write it as $$M^\pi(X \vert s, a) = \mathrm{Pr}(X \vert s, a) + \gamma \mathbb{E}_{s^\prime \sim P(\cdot \vert s, a), a^\prime \sim \pi(\cdot \vert s^\prime)}\left[\mathrm{Pr}(s_{t+1} \in X \vert s^\prime, a^\prime, \pi)\right]\;.$$

Which gives rise to the measure-valued Bellman equation which we aimed to prove: $$M^\pi(X \vert s, a) = \mathrm{Pr}(X \vert s, a) + \gamma \mathbb{E}_{s^\prime \sim P(\cdot \vert s, a), a^\prime \sim \pi(\cdot \vert s^\prime)}\left[M^\pi(X \vert s^\prime, a^\prime)\right]\;\square$$

Expressing the Q-Value Function Using the Successor Measure

So far, we’ve defined the successor measure $M^\pi(X \vert s, a)$ as the discounted probability mass of visiting a set of states $X$ in the future under policy $\pi$. But how does this relate to the actual goal of reinforcement learning, which is to maximize cumulative reward?

It turns out that the $Q$-value function, which tells us the expected return for taking an action in a state, can be directly computed from the successor measure. This connection is extremely useful because it allows us to express policy evaluation in terms of state occupancies, without needing to explicitly simulate future trajectories. Furthermore, as you will see, it allows us to decouple the successor measure from the reward function, which will allow for learning without any reward function.

By definition, the action-value function for a given reward function $r: \mathcal{S} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ is:

\[Q^\pi_r(s,a) = \mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{t=0}^\infty\gamma^t r(s_{t+1})\vert s, a, \pi\right]\;.\]Rewriting this expectation in terms of the successor measure, we obtain:

\[Q^\pi_r(s,a) = \int_{s^\prime \in \mathcal{S}} M^\pi(ds^\prime \vert s, a)r(s^\prime)\;.\]This equation tells us that the Q-value function is just an integral over the successor measure, weighted by the reward function $r(s^\prime)$. It is important to note that here $M^\pi(ds^\prime \vert s, a)$ represents an infinitesimal probability mass assigned to the small region around $s^\prime$.

We will once again prove this equivalence in the proof box below.

Proof: Using linearity of expectation: $$Q^\pi_r(s, a) = \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t \mathbb{E}\left[r(s_{t+1}) \mid s, a, \pi\right]\;.$$

By the law of total probability, the expectation over future states can be rewritten as: $$\mathbb{E}[r(s_{t+1}) \mid s, a, \pi] = \int_{s^\prime} \Pr(s_{t+1} = s^\prime \mid s, a, \pi) r(s^\prime) ds^\prime\;.$$

Substituting this into the summation: $$Q^\pi_r(s, a) = \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t \int_{s^\prime} \Pr(s_{t+1} = s^\prime \mid s, a, \pi) r(s^\prime) ds^\prime\;.$$

Rearranging the summation and the integral (assuming that this is possible): $$Q^\pi_r(s, a) = \int_{s^\prime} \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t \Pr(s_{t+1} = s^\prime \mid s, a, \pi) r(s^\prime) ds^\prime\;.$$

From our definition of the successor measure, we recognize that: $$M^\pi(ds^\prime \mid s, a) = \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t \Pr(s_{t+1} = s^\prime \mid s, a, \pi) ds^\prime\;.$$

Thus, we obtain: $$Q^\pi_r(s, a) = \int_{s^\prime \in S} M^\pi(ds^\prime \mid s, a) r(s^\prime)\;\square$$ which is exactly what we wanted to prove.

Intuitively, this representation of the Q-function means the following:

- $M^\pi(s^\prime \vert s, a)$ represents how much influence state $s^\prime$ has on the future when starting from $(s, a)$.

- The reward function $r(s^\prime)$ determines how valuable each state is.

- The Q-function simply combines these two quantities, giving more weight to states that are both frequently visited and have high rewards.

This formulation is powerful because it means that once we know the successor measure, we can compute Q-values for any reward function immediately—without re-running reinforcement learning. If we change the reward function, we only need to update the integral, rather than recomputing the entire policy from scratch.

Now that we’ve seen that Q-values can be computed directly from the successor measure, a natural question arises:

How can we efficiently store and compute the successor measure without needing to explicitly track every possible future state?

This is where Forward-Backward (FB) Representations come into play. Instead of storing a full probability measure over future states, we will learn compact representations that approximate the successor measure efficiently.

In the next section, we introduce FB Representations, which allow us to express the successor measure as the inner product of two learned functions. This will give us a structured way to reuse learned knowledge across multiple tasks while keeping computations efficient.

Forward-Backward Representations: Structuring the Successor Measure

In the previous section, we introduced the successor measure, which captures how an agent moves through an environment when following a given policy. While this measure is a powerful tool for understanding state occupancies, storing and computing it explicitly can be infeasible—especially in large or continuous state spaces. If we wanted to store $M^\pi(s^\prime \vert s, a)$ exactly for every possible pair $(s,a)$, we would need to keep track of an entire distribution over future states for every starting point. This quickly becomes computationally intractable.

Instead of explicitly storing $M^\pi$, we can learn a compact, structured representation of it using Forward-Backward ( FB) Representations. The key idea behind FB Representations is to approximate the successor measure using two components:

- A forward embedding $F^\pi(s,a)$ which captures how state-action pairs influence future states.

- A backward embedding $B(s^\prime)$ which captures how states are reached from past states and actions.

This allows us to efficiently approximate the successor measure as an inner product between these learned embeddings. The FB representation aims to learn a finite-rank approximation:

\[M^\pi(X \vert s, a) \approx \int_{s^\prime \in X} F^\pi(s, a)^\intercal B(s^\prime) \rho(ds^\prime)\;.\]TODO: Is there some bound of closeness on this term?

where:

- $\rho^\pi(X) = (1-\gamma)\mathbb{E}_{s\sim\mu, a\sim\pi(\cdot, s)}\left[M^\pi(X\vert s,a)\right]$ is the stationary discounted distribution of $\pi$ ($\mu$ is a distribution over initial states).

- $F^\pi: \mathcal{S} \times \mathcal{A} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^d$ is the forward embedding, encoding how actions influence future states.

- $B: \mathcal{S} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^d$ is the backward embedding, encoding how states contribute to state occupancy.

This formulation means that, instead of storing a high-dimensional probability measure, we only need to store and update two low-dimensional representations, making computation and generalization across tasks significantly easier.

Expressing the Q-Function with FB Representations

Using the approximation to the successor measure above, we can now express the Q-value function in terms of FB representations. Recall that the Q-function is computed as:

\[Q^\pi_r(s,a) = \int_{s^\prime \in \mathcal{S}} M^\pi(ds^\prime \vert s, a)r(s^\prime)\;.\]Substituting the FB decomposition, we get:

\[Q^\pi_r(s,a) = \int_{s^\prime \in \mathcal{S}} F^\pi(s, a)^\intercal B(s^\prime) \rho(ds^\prime)r(s^\prime)\;.\]If we now define a task encoding vector as:

\[z = \mathbb{E}_{s \sim \rho}\left[B(s)r(s)\right]\;.\]We can rewrite the Q-function as:

\[Q^\pi_r(s,a) = F^\pi(s, a)^\intercal z\;.\]This means that once we have learned $F^\pi(s,a)$ and $B(s)$, we can compute Q-values for any reward function instantly by computing the appropriate task vector $z$. This is extremely powerful, as it allows an agent to generalize across multiple tasks without retraining (zero-shot). The task encoding vector $z$ acts as a mapping of the reward onto the backward embedding $B$.

FB Representations for Multiple Policies

Instead of learning a single policy, we can generalize this framework to a distribution of policies indexed by a latent variable $z$ which controls task-specific behavior. This approach, proposed by TODO, learns a unified representation space for both embeddings and policies.

The key equations for this generalization are:

\[\begin{cases} M^\pi_z(X \mid s, a) \approx \int_{s^\prime \in X} F(s, a, z)^\top B(s^\prime) \rho(ds^\prime), & \forall s \in S, a \in A, X \subset S, z \in Z, \\ \pi_z(s) = \arg\max_a F(s, a, z)^\top z, & \forall (s, a) \in S \times A, z \in Z. \end{cases}\]where:

- $ Z \subseteq \mathbb{R}^d $ is the space of task encoding vectors (e.g., a unit hypersphere with radius $\sqrt{d}$).

- $ \pi_z(s) $ is the policy associated with task encoding $ z $.

- The same task encoding $ z $ parameterizes both $ F $ and $ \pi $ ensuring consistency across tasks.

With this representation, The policy $\pi_z(s) = \arg\max_a F(s, a, z)^\top z$ naturally follows from the learned representations, providing an efficient way to optimize for different tasks with any reward function.

TODO: Go into more detail on why this is possible.

Learning Forward-Backward Representations

So far, we have established that FB representations allow us to efficiently approximate the successor measure using a low-dimensional factorization. However, to be useful in practice, we need to learn the forward and backward embeddings $F(s,a,z)$ and $B(s)$ in a way that ensures they accurately capture the successor structure.

The key idea is to train these representations to satisfy the Bellman equation for successor measures, which we saw in section TODO, ensuring that they correctly predict the future state distribution. This leads to a temporal difference (TD) loss function, which aligns $F$ and $B$ through self-supervised learning.

Learning via Temporal Difference Loss

To ensure that $ F $ and $ B $ satisfy the successor measure recursion, we minimize the Bellman residual, which comes from the previously seen equation from section TODO:

\[M^\pi(s^+ \mid s, a) = P(s^+ \mid s, a) + \gamma \mathbb{E}_{s^\prime, a\prime \sim \pi} \left[M^\pi(s^+ \mid s^\prime, a^\prime)\right].\]The learning objective is then constructed by taking the squared Bellman residual as the primary loss term with an added regularization term:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{FB}}(F, B) = \mathbb{E}_{z \sim \nu, (s,a,s^\prime) \sim \rho, s^+ \sim \rho, a^\prime \sim \pi_z(s^\prime)} \left[ \left( F(s, a, z)^\top B(s^+) - \gamma \overline{F}(s^\prime, a^\prime, z)^\top \overline{B}(s^+) \right)^2 \right]\] \[- 2\mathbb{E}_{z \sim \nu, (s,a,s^\prime) \sim \rho} \left[ F(s, a, z)^\top B(s^\prime) \right]\;.\]where:

- $\nu$ is a distribution over $Z$, and $ (s, a, s^+) \sim \rho $ represents sampled transitions from the environment.

- $ \overline{F}, \overline{B} $ denote stop-gradient operations to prevent instability in training.

- The first expectation term ensures that $ F(s, a, z)^\top B(s^+) $ aligns with the Bellman recursion.

- The second expectation term acts as a regularization term, ensuring that $ F(s, a, z) $ and $ B(s) $ form a structured representation space by attempting to maximize the cosine similarity between them.

The derivation of this loss can once again be found again below.

Proof: Substituting the FB decomposition $ M^\pi(s^\prime \mid s, a) \approx F(s, a, z)^\top B(s^\prime) $, we approximate the successor measure equation as: $$F(s, a, z)^\top B(s^+) \approx P(s^+ \mid s, a) + \gamma \mathbb{E}_{s^\prime, a^\prime \sim \pi} \left[ F(s^\prime, a^\prime, z)^\top B(s^+) \right]\;.$$

Since we are not explicitly modeling the transition probability $ P(s^+ \mid s, a) $, we replace it with a learned approximation directly through $ F(s, a, z)^\top B(s^+) $, leading to the residual: $$\delta(s, a, s^+, s^\prime, a^\prime, z) = \left( F(s, a, z)^\top B(s^+) - \gamma F(s^\prime, a^\prime, z)^\top B(s^+) \right)\;.$$

Minimizing this **Bellman residual** ensures that $ F(s, a, z) $ correctly models the recursive nature of the successor measure.

By minimizing this loss, we ensure that FB representations accurately approximate the successor measure while maintaining temporal consistency.

Training the Policy with FB Representations

Since the policy is defined as:

\[\pi_z(s) = \arg\max_a F(s, a, z)^\top z,\]in continuous action spaces, the $ \arg\max $ operation is not directly differentiable. Instead, we approximate it via policy learning by training an actor network to minimize:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{actor}}(\pi) = -\mathbb{E}_{z \sim \nu, s \sim \rho, a \sim \pi_z(s)} \left[ F(s, a, z)^\top z \right].\]This loss function ensures that the policy $ \pi_z(s) $ selects actions that maximize the learned Q-function. By minimizing $ \mathcal{L}_{\text{actor}} $, the policy learns to align its actions with those that maximize future state occupancy for a given task encoding $ z $. This method allows the policy to efficiently adapt to different tasks by leveraging the learned FB representations.

Zero-Shot Inference with FB Representations

TODO: Get a bit more into specifics and details here

A major advantage of FB representations is their ability to generalize across multiple tasks without retraining, enabling zero-shot inference. Given a dataset of reward samples $\{(s_i, r_i)\}_{i=1}^{n}$, the optimal task encoding for reward maximization is computed as:

\[z_r = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} r(s_i) B(s_i).\]This allows an agent to instantaneously derive the optimal policy for any reward function simply by computing $z_r$, without requiring additional reinforcement learning. Similarly, for goal-reaching tasks, where the agents needs to reach a certain state $s \in \mathcal{S}$, the optimal goal-conditioned task encoding is:

\[z_s = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} r(s_i) B(s_i) = 1\left[s_i = s\right] B(s_i) = B(s).\]This means that an agent can directly execute the policy $\pi_{z_s}$ to reach a specific state without additional planning.

Imitation Learning with FB Representations

FB representations also provide a framework for imitation learning, allowing an agent to infer a policy directly from expert demonstrations. Given a trajectory $\tau = (s_1, \dots, s_n)$ collected from an expert policy, the zero-shot inference of the task encoding is given by:

\[z_\tau = \mathbb{E}_{\text{FB}}(\tau) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} B(s_i).\]This inferred $ z_\tau $ serves as a representation of the expert’s behavior, allowing the agent to execute $ \pi_{z_\tau} $, effectively mimicking the expert without requiring additional fine-tuning.

Zero-shot inference via FB representations enables agents to rapidly adapt to new rewards, goal-reaching tasks, and imitation learning, making it a highly flexible and scalable approach to policy learning.

Limitations of FB Inference

While FB models provide a powerful approach for generalization, their effectiveness depends on:

- State coverage: If the training dataset $\rho$ does not adequately cover the environment, FB models may struggle to generalize.

- Embedding capacity: When the embedding dimension $d$ is small, the learned representations may collapse to a few policies, limiting adaptability.

- Offline training bias: Since FB models are trained on pre-collected data, they may inherit biases from the dataset, limiting real-world performance.

However, when trained with sufficient data and representation capacity, FB models can learn optimal policies for any reward function and enable fast adaptation in diverse settings.